| | NEWS

Bearer Of The Undying Torch: An Appreciation of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Drachman zt'l, in the Seventy-fifth Year Since His Petirah

By Moshe Musman

The story of Rabbi Dr. Bernard Drachman, who passed away fifty years ago, contains important lessons for understanding about the survival of Torah in the spiritually barren and desolate land that America was a hundred years ago. Rabbi Drachman grew up in a thoroughly American environment, but he nonetheless became firmly and deeply committed to Torah true principles that were, in his person, completely at ease with his all-American heritage.

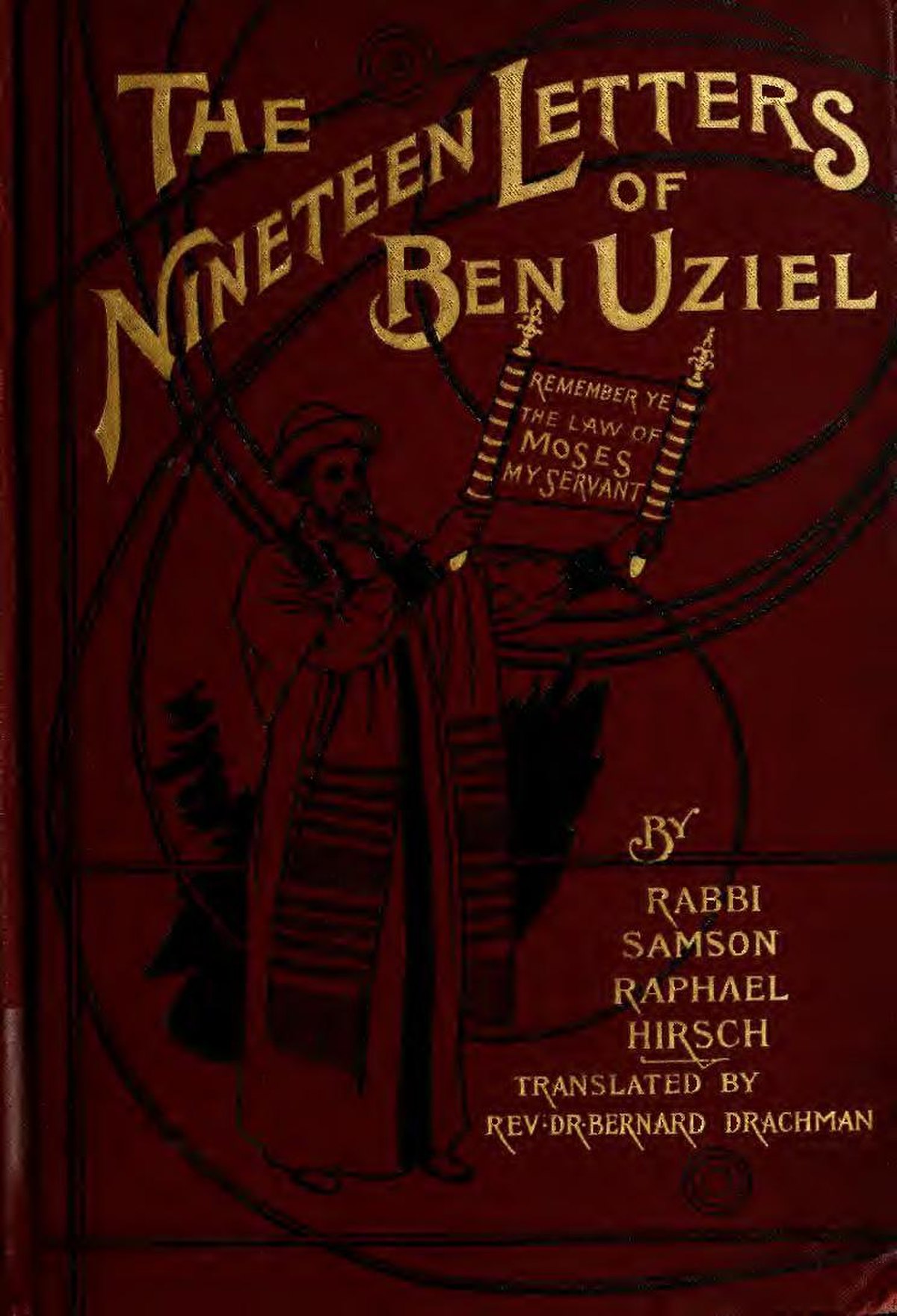

Rabbi Drachman saw, with a fresh and open American eye, the deep and sincere emunah and shemiras mitzvos of the Jews of a small German town, the flowering of HaRav Hirsch's Frankfurt, as well as the vitality of eastern Europe. He attended the funeral of Sir Moses Montefiore, officiated at the funeral of Harry Houdini and was on familiar terms with Seth Low, one of the legendary presidents of Columbia University. He also translated Hirsch's The Nineteen Letters and was responsible for Mordechai Kaplan's dismissal from his post as a rabbi in New York City in an Orthodox congregation solely because of the latter's heretical views. His fascinating story helps us understand some of the important roots of the American Jewish community.

In the first part, we read of Rabbi Drachman's youth in Jersey City, and education in Columbia College and Breslau. In Europe he was also deeply impressed with the wholesome and sincere faith and practice of religion that he encountered there. In this week we read of his career as a champion of traditional Judaism while thoroughly at home in the American milieu.

Almost all the material in this article is based on Rabbi Drachman's autobiography The Unfailing Light.

Part III

Founding of the Jewish Theological Seminary

In November 1885, shortly after Rabbi Drachman's return from Germany, the American Reform leaders held a widely publicized conference in Pittsburgh, at which they loudly proclaimed their movement's negation of some of the most fundamental and important teachings of Judaism.

Many Orthodox and Conservative leaders were shocked by the frank heresy and the wide publicity it garnered, and feared that unless some action was taken, there would be no future at all for Orthodoxy in America. In those times, the lines between Orthodox and Conservative were not as sharply drawn as they later were. The apikorsus of the early adherents of the Conservative ideology was not as evident then as today. Indeed, not all of them may have been apikorsim. In general, Conservatives were regarded then as tending to be more lenient in their rulings but as being in basic sympathy with the Orthodox viewpoint and conforming basically to orthodox practice. Rabbi Drachman always counted himself among the Orthodox. At a conference of Orthodox and Conservative leaders held in January 1886, it was decided to found the Jewish Theological Seminary, where rabbis would be trained who were familiar with America and who would uphold authentic Judaism.

Despite the involvement of some Conservatives in the conference, Rabbi Drachman relates that the Seminary's founding principles were those of unambiguous adherence to the tenets of Orthodox Judaism, "as ordained in the Law of Moses and expounded by the prophets and sages of Israel in Biblical and Talmudic writings" — a quote from the Seminary's charter of incorporation.

Rabbi Drachman took up a teaching post at the Seminary, where he remained until its reorganization under Solomon Schechter in 1901 when he was essentially dismissed as the Seminary became increasingly alienated from the Orthodoxy of its founding days. There is no hint of ideological differences in Rabbi Drachman's own account, but the editor notes: [1] Rabbi Drachman was told there were "budgetary" problems that precluded his continuing to teach there; [2] Despite the fact that Rabbi Drachman had served as dean for several years, he was the only one whose position was cut as a result of these purported financial straights; [3] The ideological drift of the Seminary was distinctly in the "liberal" direction, and Rabbi Drachman increasingly did not fit in there ideologically.

After about a year of trying to maintain both his teaching position in New York as well as the post of a congregational rabbi in Newark, New Jersey, Rabbi Drachman resigned from the latter post and moved to New York. Rabbi Drachman had accepted the rabbinical post around a year earlier. The congregation had informed him of their serious desire to uphold genuine Judaism in their congregation, which they were doing, with one sole exception. While noting that strict consistency may have required him to refuse them on this account, he nevertheless responded positively to their call because he saw that in this instance, they were acting mistakenly, rather than out of a desire for change and because they informed him of their anxiety to avoid being led by a Reform rabbi who would lead them away from observance.

In the Eye of the Storm

Early in 1887, Rabbi Drachman was overjoyed to be engaged as the rabbi of a congregation that had relocated to a new synagogue in upper New York City. The congregation had been established in 1847 and its first house of worship was on the lower East side. It had always adhered to Orthodox tradition and despite the fact it was now made up in good part of the founders' Americanized offspring, the indications were that this would continue to be the case.

Around a year after this appointment, Rabbi Drachman married the eldest daughter of Mr. Jonas Weil, a warmly and genuinely Orthodox man who was a typical example of the type of a fine, old-fashioned German Jew. The Weil family came from Baden, Germany and after arriving in America, they had risen to a degree of affluence that enabled Mr. Weil to devote himself mainly to communal work.

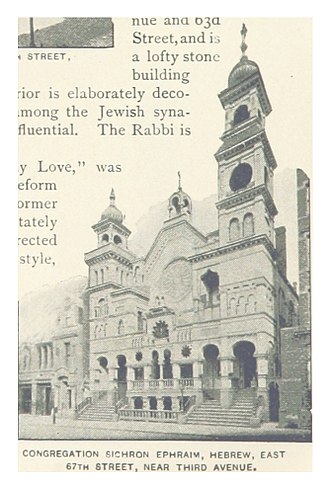

Congregation Zichron Efriam building

Even before Rabbi Drachman's marriage, trouble had begun to brew in his congregation, in the form of demands by some elements in the congregation for reforms. As was usual in such cases, the innovators began by agitating for the "mere" alteration of the seating arrangements in the synagogue, ostensibly a minor matter.

Rabbi Drachman explained to them the basis for the separation of men and women, showing that it was firmly grounded in the gemora, and adding that there was no authority in existence that had the power to modify or abrogate any such institution of Jewish law or custom. This unequivocal ruling seemed at first to lay the matter to rest but shortly after Rabbi Drachman's marriage, the agitation was renewed with increased intensity.

The reforming members demanded and were successful in convening a general meeting to discuss the matter. Almost all the members attended as did their rabbi and his father-in-law, who had also joined the congregation.

When the issue of whether or not to introduce mixed seating was put to the vote, the members were divided exactly equally. This left the decision up to the president, who held the casting vote. He apologized to the rabbi a little shamefacedly before proceeding to declare himself in favor of the proposed reform.

Rabbi Drachman was too shocked to speak. He was unable to utter a word in response to the president's assurances that he was valued and appreciated by the congregation, who hoped that he would still retain his attachment to them. All the rabbi could do was rise and leave to go home, accompanied by his father-in-law, in the realization that there was no way that he could remain in his position.

To his relief and delight, he was fully supported in this view by his father-in-law, who encouraged him to deliver a farewell sermon in which he would mince no words in telling the congregation exactly what he thought of their position. Convinced that this would create a kiddush Hashem, Rabbi Drachman spent the two days remaining before Shabbos in the preparation of this sermon.

He gave no advance hint of what he would speak about until the sefer Torah had been returned to the oron hakodesh and he ascended the podium.

Speaking with unusual fire in his voice, he then told the congregation that a rabbi had to be a true and sincere interpreter of G-d's word and that they, no less than he, were bound to accept the true doctrines of Judaism. It was not for human beings to presume to set aside any of the Torah's laws on the grounds of their being unimportant for we are unable to weigh one commandment against another. Since they had flouted these principles, he no longer considered a rabbinical position in their congregation a worthy one and he informed them that, with the conclusion of that service, he would cease to be their leader.

The considerable agitation that Rabbi Drachman had experienced before he spoke was now the lot of the congregants, whose excited conversation filled the synagogue at the conclusion of the sermon. Calm and collected, Rabbi Drachman left the synagogue after musaf in the company of his father-in-law, declining to enter into conversation with anyone.

The incident created a sensation in New York, throughout the country and, to an extent, in the entire Jewish world. Rabbi Drachman was interviewed by both the Jewish and the general press, who were eager to hear his explanation for his action. The story was reported in the Jewish newspapers of both Western and Eastern Europe.

Rabbi Drachman received many letters, mostly from Orthodox Jews who expressed their approval of his stand but also several from Reform Jews who denounced him as a reactionary and a fanatic. The realization that he had become personally identified with the cause of Orthodox Judaism in the public eye increased Rabbi Drachman's resolve to dedicate all his strength to defending and furthering Orthodox Judaism among his American Jewish brethren. For this however, he felt that he would need a suitable position as rabbi of a congregation.

Due to the publicity attracted by his strong stand, he received several invitations from Orthodox congregations, none of which however, seemed suitable ground for the work he hoped to do, either because of their out-of-town locations or because of the makeup of their membership, worthy and sincerely Orthodox though they were.

After spending some time observing his son-in-law's difficulties in deciding where to throw in his lot, Mr. Weil suggested that he start his own congregation. Those who joined would then have chosen him and his ideas, rather than the other way around. This would leave him free to carry out his plans for furthering Orthodoxy in the way he envisaged.

In response to letters sent out by Rabbi Drachman and Mr. Weil, responses were received from almost two hundred family heads who were interested in joining the proposed congregation. These men represented the best of the city's Orthodox elements and came from diverse Jewish backgrounds, including some of Russian, Polish, Hungarian and German ancestry, as well as a number of American birth.

In 1889, a constitution was adopted and a board of trustees elected and, in the same year, the cornerstone of a building was laid on a piece of land that had been acquired mainly through Mr. Weil's efforts and generosity. The synagogue of Congregation Zichron Efraim, (named after Efraim Weil, the father of Mr. Weil and his brother, who had donated substantially towards the new building) was dedicated in the late Summer of 1890, and the first services were held for the Yomim Noraim of 5651.

A Voice for Orthodoxy

At the age of twenty-nine, Rabbi Drachman had thus become the founding rav of a new kehilla which, due to the circumstances of its establishment, was something of a rallying point for those who wished to see Orthodoxy take root in America.

Besides the tefillos and shiurim which were held at Zichron Efraim, the community ran a number of other projects for heightening Jewish knowledge and awareness. A Hebrew School was opened immediately which quickly achieved great popularity and, through the decades, provided thousands of children with the basic knowledge and understanding of Judaism that would anchor them firmly in their ancestral religion throughout their lives. Activities, such as the formation of Young People's Societies and public lectures, were encouraged, which brought young and old members together outside the regular tefillos, with the aim of heightening interest and strengthening commitment to Judaism.

There was much to be accomplished outside Zichron Efraim as well. Besides teaching for many hours each week, giving frequent talks and lectures and submitting numerous articles and letters to the Jewish and sometimes the general press, Rabbi Drachman organized The Jewish Endeavor Society, an organization for adolescents, aimed at providing a strong positive Jewish influence on the emerging adults, whose years of study in Hebrew School as children could not provide them with all the necessary equipment for meeting the influences of the wider world and remaining steadfast as religious Jews. When this organization ceased to exist, the same work was undertaken by the then-new Young Israel movement, whose efforts Rabbi Drachman warmly supported.

Another of the causes Rabbi Drachman worked for tirelessly was the upholding of Shabbos observance. Tragically, it seemed that for many of the new immigrants, arrival in America was synonymous with ceasing to keep Shabbos. Undoubtedly, the main cause of this situation, which had tragic consequences for many, many families, was the difficulty in obtaining employment that would allow Shabbos to be taken off.

Together with several other concerned individuals Rabbi Drachman founded Tomchei Shabbos. The organization's main work was interceding with employers on behalf religious Jews who found themselves coerced economically into working on Shabbos. Happily, this effort yielded positive results.

It was also planned to run an employment bureau which would bring shomrei Shabbos workers and employers together. A third way of tackling the problem was by the reform of the so-called "blue laws" that designated Sunday as the official day of rest. Numerous times, Rabbi Drachman led attempts to introduce legislation that would grant the Shabbos observer the same legal status as the Sunday observer, entitling him to take his day of rest on Shabbos. Despite his dogged pursuit of this goal for many years, including many personal trips to the state capitol in Albany, Rabbi Drachman was unsuccessful in achieving this aim.

In 1899, Rabbi Drachman published his first literary work, an English translation of HaRav Hirsch's The Nineteen Letters. In 1905 he published, From The Heart Of Israel, a book of stories and incidents illustrative of Jewish character and life. Looking At America, published in 1934, concerned many of the problems and issues affecting American society at large, rather than specifically Jewish topics. Rabbi Drachman was active in the world of Hebrew scholarship and was also a contributor to the Jewish Encyclopedia.

End of Part III

Click here for Part II

Click here for Part IV

|