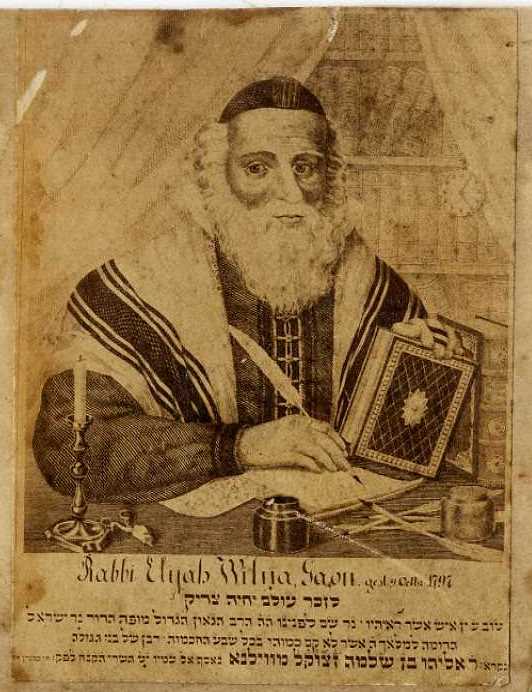

One of the traditional drawings of the Vilna Gaon

Several divrei Torah mostly about Succos from the Gra.

"Hide Them In A Succa"

From The Vilna Gaon

"Hide them in a succa from a quarrel of tongues." (Tehillim 31:21)

The mitzva of succa has the power to subdue the inclination to speak loshon hora and other forms of forbidden speech.

The Hebrew word "succa" is composed of four letters, each of which belongs to a phonetically different group of letters formed by various parts of the mouth:

The samech belongs with the "ZaSShRaTz" letters (zayin, samech, shin, reish, tzaddi) formed by the teeth.

The vov is with the "BUMaF" letters (beis, vov, mem, pei) formed by the lips.

Kaf is with the "GIChaK" letters (gimel, yud, kaf, kuf) which are formed by the palate.

And the hey is one of the guttural "AHaCh'Ah" letters (alef, hey, ches, ayin) formed by the throat.

The fifth category, the "DaTLaNaT" letters (dalet, tes, lamed, nun, tov) formed by the tongue, is not represented at all in the word "succa." When forming the other letters, the teeth, lips, palate and/or throat surround the tongue to protect it from speaking loshon hora. The tongue, in other words, is "hidden" by them. This then is the explanation of the posuk, "Hide them in a succa from a quarrel of tongues."

"You Shall Dwell In Succos"

From The Vilna Gaon

Most mitzvas are performed with one of the body's limbs: the mouth, the hand or foot and so on. There are only two mitzvos into which a Jew enters with his whole body: succa and Eretz Yisroel. This is hinted at in the posuk, "And it was when His succa was in Shalem and His dwelling place in Zion." (Tehillim 76:3) "And it was when in Shalem" — which mitzva does one do "beshalem", completely, with one's whole body?

"Succo," the mitzva of succa, and also "me'onaso beTzion" — living in Eretz Yisroel.

How do we know that Avrohom Ovinu fulfilled the mitzva of succa? In the medrash we find: "And Hashem blessed Avrohom bakol — with everything." "Bakol" — this is succa." What allusion does the medrash find in the word "bakol" to succa? The Gaon explains that the word "bakol" hints to the first letters of the pesukim which deal with the mitzva of succa:

Beis: "Besuccos teishvu.."

Kaf: "Kol ho'ezrach..."

Lamed: "Lema'an yeid'u..."

"Se'ir Izzim"

From The Vilna Gaon

Listing the offerings for Succos, the Torah writes for the first day, "one se'ir izzim for a chattos," repeating the same descriptive phrase for the second days' chattos tsibur.

For the third day however, the Torah writes simply, "one se'ir chattos." For the fourth it writes again, "one se'ir izzim..." but on the remaining days, it writes merely "one se'ir chattos."

Why on the first, second and fourth days is the phrase "se'ir izzim" used while on the third, fifth, sixth and seventh days the Torah writes simply "se'ir"?

The explanation is, says the Gaon, that the seventy porim which we offer on the days of Succos correspond to the seventy nations of the world. The Zohar states that the roots of all of the seventy go back to Yishmoel and Eisov from whom all the other nations derive their sustenance. The baalei kabbalah explain further that Yishmoel is called "se'ir izzim" while Eisov is called simply "se'ir."

As the nations come principally from Yishmoel and Eisov, thirty-five of the porim should be brought for each of them. Thus, the thirteen porim of the first day are for Yishmoel (who goes first because he is Avrohom's son whereas Eisov is the son of Yitzchok) and for this reason the Torah writes "se'ir izzim," alluding to Yishmoel. On the second day, a further twelve are offered for Yishmoel, totaling twenty-five, and hence the phrase is used again.

The third day's offerings cannot be for Yishmoel for there are eleven porim which would make thirty-six instead of thirty-five, so the third day is for Eisov, and the Torah writes just "se'ir."

The ten porim of the fourth day go to make up Yishmoel's thirty-five thus "se'ir izzim" is used, and for the remaining days, which make up Eisov's total, "se'ir" alone is used.

Rain On Succos

From The Vilna Gaon

"If rain fell on chag... it is like a servant who came to mix a cup for his master and he spilled the container in his face." (Succa 28)

Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are days of judgment. The days of Succos with their mitzvos of succa and lulav are days of mercy whose purpose is to mellow the harshness of the dinim through the mitzvos which surround us. When rain falls, forcing us to leave the succa, it is a sign that HaKodosh Boruch Hu does not wish to mellow the din, as it were, for without rachamim, the din retains its original strength.

This is what the comparison to the servant hints at. Mixing the wine with water is necessary to dilute the strength of the wine. When the master spills the water, he shows that he does not want the strength of the wine to be lessened. This is what rain on Succos means; it is a hint from shomayim that the days of rachamim are being prevented from weakening the strength of the din.

"Said Koheles..."

From the Vilna Gaon

"Vanity of vanities, said Koheles, vanity of vanities, all is vanity."

There are seven "vanities" in this posuk (the word "hevel", in the singular form, occurs three times and the plural "havolim," occurs twice, making a total of seven). The words "said Koheles" appear after three "havolim," when it would seem to be more appropriate for them to be either at the beginning or the end of the posuk.

According to the Mishna (Avos 5:21), for the first twenty years of a person's life, he advances: at age five years to mikra, ten for mishna etc.). From the age of ninety onwards is the time of decline (ninety years old to be bent..). The years between the ages of twenty and ninety are the middle years, a time of stability, exposed to life's vanities (twenty years old to chase, thirty years old for strength....). Even "understanding" and "counsel" which are mentioned during this time have no positive value in and of themselves. They are merely abilities which can be used for good or bad according to a person's will and they have no intrinsic value.

The seven "havolim" in the posuk correspond to the seven decades in the mishna between the ages of twenty and ninety (for chasing, strength, understanding, counsel, old age, hoary old age, and might).

Shlomo Hamelech lived for fifty-two years. He therefore lived for only three of the periods of "hevel" of the middle years. This is why he said, "Hevel havolim omar Koheles..." I myself, said Shlomo Hamelech, have lived through only three of the "havolim" and have personally examined them but I know that "havel havolim, hacol hevel." The remaining years of middle age are also vanity.

Ten Extra Minutes Of Sleep

HaRav Chaim Yaakov Reznik zt'l, av beis din of Wilkomir, writing in a letter, describes a wonderful incident involving the Vilna Gaon which took place during the Gaon's self-imposed exile through the towns of Lithuania, when he came to a place named Maratz:

When the people of Maratz heard that the Gaon of Vilna, who was like one of Hashem's mal'ochim, was staying in their city, there was a great commotion. The city was in turmoil and for the entire night the Gaon spent there, nobody slept, neither young nor old, women nor children. They thought hard of some way they could merit seeing the face of the holy Gaon and finding out something of how he conducted himself and how he spent the night.

It was finally decided to bring ladders tall enough to reach the windows of the second story room of the house which the Gaon was staying in and to secretly observe the deeds and customs of the holy man. They did not dare to go right inside the Gaon's lodgings and observe him directly for the fear of the Gaon's holiness had fallen on them. They were also afraid to go inside in case they would disturb the Gaon's rest. However, they could not keep themselves from climbing up the tall ladders on the outside and watching through the windows what the Gaon did.

Whoever merited to climb up the ladder outside the Gaon's lodgings that night, and look inside at the Gaon sitting and learning with all the glory of his genius and his great kedusha, felt himself, and seemed also to the other townspeople, to be the happiest person in the world.

The elders, may their neshamos rest in Gan Eden, told me that their fathers told them something wondrous about that night. All night long there was perfect order and discipline among the large crowd of people who had come to watch the Gaon. People did not push or pressure each other. Not one voice was raised in anger or confusion. Instead, a holy silence held sway over all those who had gathered to see the Gaon.

The elders of the past generation said that the Gaon's great kedusha and righteousness had an effect on everyone and they all experienced a feeling of holiness and majesty, unlike any other, which they did not forget for years afterwards.

When the people of Maratz placed the ladders on the wall of the Gaon's lodgings, they arranged to take turns to go up to the top of the ladder, to wait a while and watch the Gaon and then come down letting someone else go up to see the Gaon. They were not allowed to tarry on the ladder for they all wanted to see the holy man from Vilna.

Suddenly, after midnight, the saddening report spread through Maratz that the holy Gaon of Vilna had woken up from his short night's sleep [as is well known, the Gaon slept very little at night], and had said, in a trembling, horrified voice, that in Maratz he had been overcome by tiredness and had slept during that night about ten minutes more than usual, which was ten minutes of avodas Hashem missed. Ten minutes extra sleep for a Gaon and a saint like him represents a great loss and damage in Torah and mitzvos. The Gaon was very upset about this and with a broken and contrite heart, said the following, "In Maratz, one sleeps."

As soon as the Gaon's anguish over his ten minutes of extra sleep became known to the people, they were also very upset that such a thing had happened in their city, that a such a pure, holy man like the Gaon of Vilna had lost ten minutes of avodas Hashem in their city. Chazal said (Sanhedrin daf 71b) that sleep for tzadikim is bad for them and for the world. All the town's joy at receiving the Gaon changed into grief over the extra ten minutes of sleep that their town had caused, and the pain it had brought him.

My father, HaRav HaGaon Rav Beinish zt'l, who served as rav in Maratz for about sixty years, told me that he remembers as a child, hearing from the reliable elders of the town, who had heard from their own fathers, that the Gaon later restored the lost time. When he came back from Sarahie to Vilna, when the quarrel in Vilna had died down, he again travelled through Maratz and spent a night at his first lodgings, in the home of Reb Leib the son of Reb Zalman. During that night the Gaon of Vilna slept ten minutes less than his usual amount in order to correct the sin of his ten minutes extra sleep from the first time.

When the Gaon saw that Hashem yisborach had allowed him to set right the ten minutes extra sleep, he was very happy. It became known straight away to the people of Maratz who themselves rejoiced in the rejoicing of the Gaon of Vilna.