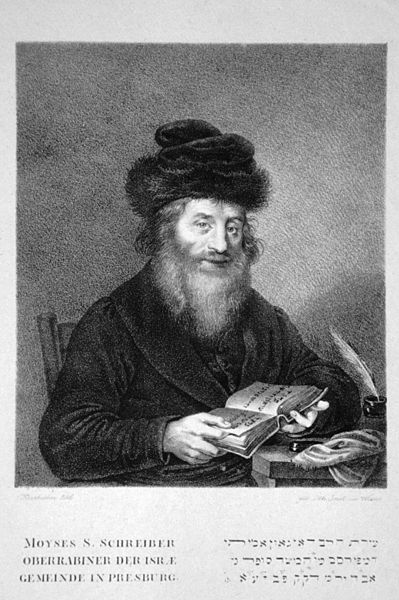

The Chasam Sofer

Pupil And Teacher

Reb Aharon held both HaRav Meshullam Iggre and the Chasam Sofer in tremendous esteem. He would repeat the story of the Chasam Sofer's visit to Pressburg, when he wanted to recite the brocho, "shecholak mechochmoso liyere'av" on HaRav Meshullam. To simply approach the godol and say the brocho was not possible so the Chasam Sofer opened up a gemora Brochos and read out from it the halacha, "One who sees sages of Yisroel says: Boruch Ato Hashem...shecholak mechochmoso liyere'av."

HaRav Meshullam, giving him an angry look, asked sharply, "Rebbe, why did the Rambam leave out this halacha?"

Without a pause, HaRav Meshullam gave the answer, "For the same reason that he left out the halacha that non fruit-bearing trees can only be planted at a distance of fifty amos from the city. The Rambam's practice is to bring only those dinim which apply today or will apply in the future, in the times of moshiach.

"Nowadays neither of these two halachos applies: the first, because we have no sage today who is on a level that the brocho can be made for him, and the second because Eretz Yisroel is uninhabited. Neither will they apply in the future: all the barren trees will then bear fruit and the whole world will be full of the knowledge of Hashem and everybody will possess great wisdom!"

"The amazing thing is though," Reb Aharon would conclude, "That the Rambam does indeed bring this very halacha, in Hilchos Brochos!"

When a recently-engaged talmid told Reb Aharon of the difficulties he was having with his father-in-law to be, who "holds of the approach of the Chasam Sofer and is not happy about learning in Kollel," Reb Aharon's answer was:

"Really? Tell him that the Chasam Sofer had a brother who had a business selling tallis decorations and who supported him. That is how the Chasam Sofer was able to sit and learn eighteen hours out of every twenty four!"

Reb Aharon had a special regard for the Chasam Sofer. He was once brought a sefer written by one of the Chasam Sofer's greatest talmidim. The sefer was about to be published and Reb Aharon was asked to write a haskomo. Reb Aharon kept the sefer for a long time without returning it, and would not write a haskomo. When he was asked why, he replied, "Going through the sefer I noticed that he disagrees with his Rebbe far too easily..."

Reb Shneur had the opportunity to repeat this story to some descendants of the author and, amazed at Reb Aharon's perception, they confirmed his judgment. In fact, they said, forty years after the Chasam Sofer passed away, his talmid, the sefer's author, went to his teacher's kever to beg forgiveness for his haste in differing with him. He brought Chazal's observation that, "A man does not fully understand his teacher's intention until forty years have elapsed," in his defense. With the added years his understanding of the Chasam Sofer's teachings had matured and deepened and he regretted his haste in contradicting him.

Reb Aharon himself felt that once he too had experienced the consequences of taking issue with the Chasam Sofer. In the course of learning through a sugya, Reb Aharon took up a position which differed from the one taken by the Chasam Sofer. It was a merely a difference in understanding, not in the halachic outcome of the sugya and Reb Aharon repeated it in a shiur on Friday night. That night, the rebbetzin suffered a burn.

On motzei Shabbos Reb Aharon said the shiur a second time and while he was doing so, his daughter sustained an injury while walking in the street. The Rosh Yeshiva saw what had happened as a sign. It seems he felt he had been wrong to publicly argue with the Chasam Sofer's conclusion. His close ones had been punished on his account while he himself had been protected by the merit of his Torah.

Signs And Portents

This was by no means the only time that Reb Aharon had experiences that he understood were messages from shomayim. In a slight digression, we will relate some of these here.

We have already mentioned at length that it was Reb Aharon's practice to carry a sefer with him wherever he travelled. Once, in his rush to leave, he forgot to take a sefer with him. It was not long before one of the maskilim came across him and asked him, "Why is such a battle being waged against us? See now, we are totally dedicated to our ideas, but as for your camp... see, you are a rav and you are going about without a sefer!"

Similarly, whenever he travelled the Rosh Yeshiva took his tallis and tefillin along with him. Once, headed for somewhere nearby, he left them at home. On the way he met another Jew who, noticing the absence of these items from his companion's belongings, began to feel quite pleased with himself.

"I am neither a rabbi or a talmid," the man said. "Nevertheless, even though I am what I am, I take my tallis and tefillin with me wherever I go."

On other occasions, Reb Aharon saw signs of concurrence and encouragement, spurring him to continue. He single-handedly mounted a campaign against a certain Torah institution that turned a blind eye to the fact that a number of its students were doing part of their studies in a Christian university. He insisted that the only aim of such a university was to ensnare Jewish neshamos. The place was, he said, a house of both apostasy and avoda zara.

At the height of this battle, while travelling in a cab, the driver happened to describe the cab's previous occupants to Reb Aharon. They had been two priests, who had sat sermonizing all the time and had left behind them publications that were full of church propaganda.

"The purpose of that journey was to demonstrate to me their methods and to warn others of the danger they pose," was the Rosh Yeshiva's conclusion. "When a man leads a battle for the sake of truth, and with pure intentions, he receives encouragement from shomayim!"

Another well-known occasion took place in Europe, during the period that Reb Aharon was heading the Yeshivas Eitz Chaim of Kletsk while his father-in-law Reb Isser Zalman, was staying with the remnant of the yeshiva in Slutsk. Reb Aharon wrote a letter to his father-in-law which expressed a wish that "...and we will read the megilla together."

Reb Isser Zalman's surprise on reading this was considerable for they were separated by the well-patrolled Polish-Russian border and each of them was struggling to sustain his own yeshiva under hostile conditions. We need not dwell at length on the full story of Reb Isser Zalman's persecutions in Slutsk. Suffice it to say that, warned of his impending arrest, he had to flee the town at a moment's notice and he found himself in Kletsk on Purim night.

"Because of that sentence in your letter I was forced to run away and come here!" Reb Isser Zalman complained to Reb Aharon. "Why did you write such a thing?"

"That sentence was a slip of the pen," the Rosh Yeshiva replied, "and I have a tradition from the Chofetz Chaim that when a thing like that happens, it is a message from shomayim!"

Another such incident involved HaRav Y. Epstein, who was a talmid of the Rosh Yeshiva's in Kletsk. He was in danger of being conscripted into the Russian army and therefore asked Reb Aharon to place him at the top of the list of applications for certificates of entry to Palestine.

Recognizing the urgency of the matter, the Rosh Yeshiva rearranged the list intending to comply with this request but found that he had somehow entered other names before HaRav Epstein's. When he saw what had happened, he set about arranging the list a second time but for some inexplicable reason, once again there were other names at the head of the list.

Realizing that this was intended as a message from above, he left the list as it was and promised his disappointed talmid that he would write to his brother-in-law HaRav Y. Z. Meltzer in Yerushalaim and ask him to personally arrange an entry permit for HaRav Epstein.

HaRav Meltzer was about to deliver a shiur when he received the letter and, after reading it, he put it in his pocket and left for the shiur. On his way he met the secretary of the Chevron Yeshiva who told him that the yeshivos had been allotted a certain number of certificates to distribute, today was the last day for submitting the list and that there was still one certificate remaining!

These were the responses of a man who lived every minute with the awareness that Hashem was with him. On one occasion, uncertain as to the correct course of action, he cast the Gaon's goral [Attributed to the Vilna Gaon, this is a method of arriving at a posuk in TaNaCh which contains a message relevant to the question of whoever is casting the goral].

It was during a period of terrible financial pressure in Slutsk. Reb Aharon was approached and begged to travel abroad to raise funds. He refused, however, remarking jokingly, "Personally, I would prefer to collect on behalf of a yeshiva whose head does not take leave to go collecting!"

Nevertheless, he cast the Gaon's goral and received the posuk [Shemos 7:9] "Say to Aharon, take your staff..."

Reb Aharon still hesitated however — he was needed in the yeshiva where he delivered his shiurim and kept the atmosphere charged. After a while though, when the situation had worsened, there was no longer any choice. Picking up the TaNaCh again he received the posuk [Bereishis 43:10], "For had we not tarried, we would by now have (been able to) returned twice!"

Accepting the Divine decree, Reb Aharon packed his bag and departed.

Once, arriving at New York's Grand Central Station on his way back to Lakewood, Reb Aharon realized that he did not have money with him for the fare. Scanning the long line of people ahead of him waiting to buy tickets, he could see nobody familiar but he nevertheless joined the end of the line. From time to time, as he waited and the line slowly moved forward, he cast a glance around but saw no one he knew. When there was just one person between him and the ticket window, Reb Aharon looked round once more and caught sight of a Lakewood avreich approaching. Signaling to him, he borrowed the fare money just as it was his turn to buy a ticket.

An Idea Of Greatness

We must now return to the starting point of our discussion: Reb Aharon's reverence for the great men of past generations. His talmid, HaRav Reuven Axelrod of Yerushalaim remembers going into Reb Aharon one day to ask a question concerning a comment made by HaRav Shlomo Eiger in his notes. Reb Aharon's opinion was different so he added a lengthy evaluation of HaRav Shlomo Eiger's greatness to the answer he gave HaRav Axelrod.

Once someone ventured to ask him about the relation between the seforim Keren Orah and Mishkenos Yaakov. First, Reb Aharon spoke about the position of prominence which the author of the Mishkenos Yaakov occupied among the talmidim of HaRav Chaim Volozhiner and only then did he grant that the Keren Orah provided a more illuminating commentary "on the daf."

On another occasion, the questioner dared to ask about the Ba'al Shem Tov and the Vilna Gaon. Again, before he spoke about the Gaon, Reb Aharon described the greatness of the Ba'al Shem, his holiness and the spiritual heights that he had attained.

While speaking about the Gaon himself, Reb Aharon would tremble, his eyes burning and his face ablaze. He would quote the words of the Gaon's sons, "The teacher of Yisroel in his generation and all the generations after...his wisdom was greater than that of the several preceding generations and from the time of the rabbanan Savorai and the geonim there had arisen none like him."

Reb Aharon himself wrote that the appearance of the Gaon was brought about by Heaven in order to strengthen the faith in Torah sages and to show, by providing the generation with a personality who towered over them, that it is impossible to measure the gedolim of past generations, both before the Gaon and since, by our own standards. The Gaon, said Reb Aharon, even with his mighty intellect, stood in awe before each utterance of Chazal's and he labored to uncover the meaning of every letter contained therein. From here we have some small inkling of the significance of a single word or phrase of Chazal's — albeit no idea whatsoever of their true depth and wisdom.

The immense importance Reb Aharon attached to the Gaon was given expression in the way he toiled over every word the Gaon wrote.

"When I come across a difficult Bi'ur HaGra, [the Gaon's commentary on Shulchan Oruch]," said Reb Isser Zalman, "I don't understand it and I carry on. My son-in-law though, will not budge from it!"

Reb Aharon could spend entire shiurim searching for ways to understand and to develop ideas, all based on a single sentence or phrase in the Bi'ur HaGra.

"Like stars which appear to be small, on account of their tremendous distance but which are really huge worlds. For they are written in a very concise style and deep and wonderful chidushim are hidden in them...and boruch Hashem I have experienced this myself a number of times."

Reb Aharon attached such importance to the Bi'ur HaGra that he regarded its knowledge as something that should be the aim of every talmid. At the beginning of a zman, remembers Rav Ezra Novick, the Rosh Yeshiva called a meeting to discuss his aims for his talmidim. "One has to want to know everything and to be in command of all hidden areas of Torah including the ma'ase hamerkavah and more, right until Shulchan Oruch with Bi'ur HaGra!"

In a hesped which he delivered for a layman who had respected talmidei chachamim and been a generous supporter of Torah institutions, Reb Aharon spoke about the gemora which says that in the future, Hashem will erect a canopy for the supporters of Torah, in the shade of the talmidei chachamim.

"For in the shade of wisdom is in the shade of money." Will their reward be only the merit of Torah, asked the Rosh Yeshiva, or will they be credited with the actual learning and understanding of the Torah they supported?

After proving that the second alternative was correct, Reb Aharon ended the hesped with this declaration: "And now, Reb Avrohom, running towards you are the Bavli and Yerushalmi, the Sifro, Sifrei, Tosefta and Mechilta, the Shulchan Oruch with Bi'ur HaGra..."

He would submit himself totally to the great sages of each generation. Once the discussion centered on the different opinions and calculations of the time of sunset. Someone pointed out that the opinion of Rabbenu Tam is contradicted by the evidence of our own eyes, for we see that night falls long before the end of Rabbenu Tam's twilight. The Rosh Yeshiva trembled when he heard this and retorted, "Rabbenu Tam kenn men nit opfregen mit'n chush!" ("It is not possible to contradict Rabbenu Tam with the evidence of our senses!")

HaRav Reuven Grozovsky, HaRav Yaakov Kamenetsky, HaRav Aaron Kotler

If The Rishonim Are Like Angels

When HaRav Yaakov Kamenetsky zt'l heard that Reb Aharon spent Shabbos in the yeshiva and took his meals with the bochurim he was dismayed.

"Is that so?" he said. "He eats in the dining room? Then the bnei yeshiva may imagine that he is a human being when in fact he is a malach!"

This was the comment of a godol beYisroel and a lifelong friend of the Rosh Yeshiva's. Just as Reb Aharon opened the door to a different perspective on the great teachers of our history, it is from the mouth of another godol, whose perceptions of gadlus are far ahead of our own, that we hear Reb Aharon spoken of as a malach.

This is in sharp distinction to the famous among the nations lehavdil, who are often revered by the ordinary person from a distance while those who lived in closer proximity to them tell a very different story. The more we learn about our gedolim on the other hand, and the greater our understanding, the more of their greatness we see. Ultimately though, while we may imagine that we understand, we are far from a true appreciation.

We will end with the comment of one of Reb Aharon's talmidim who, when approached for his recollections of the Rosh Yeshiva, thought for a moment and said:

"Chazal said, `If the rishonim are like mal'ochim, we are like humans. If the rishonim are like humans, we are like donkeys.' Why did chazal choose to draw such a sharp contrast — humans and donkeys? Besides, we already know that a rav must be like a malach, and in fact we are really none the wiser as to what he really is — has any of us ever seen a malach?

"It is this last question that chazal wanted to answer. We know the Rav is a malach but what is a malach?

"A malach for us is what a human being is for a donkey. Think for a moment how a donkey sees a human. However great its intellect, it cannot go further than its own donkey-ideas. To him, a human is like a donkey on two feet — very clever, but in donkey-fashion. A rider with his stick is also a "super" donkey, controlling all the other donkeys who walk on fours. The donkey can never comprehend a human being as being anything more than a kind of super-donkey."

"Chazal are telling us that we are like that when it comes to mal'ochim. We imagine a malach to be a spiritual being, with no physical body, that can fly around...all we are really thinking of is a human being super-intelligent perhaps, and without a body, but we can't get away from thinking in purely human dimensions which, when it comes to appreciating a malach, are quite donkey-like!"