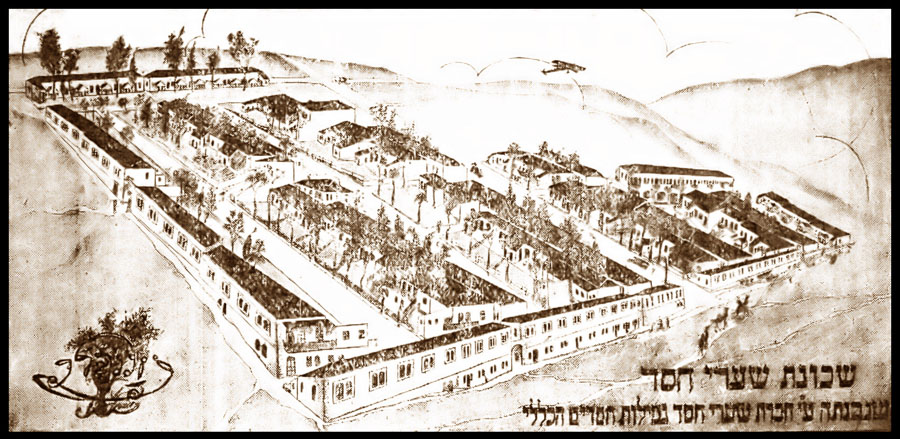

The original plan of the Shaarei Chesed neighborhood

"If You Have Learned A Lot Of Torah, Do Not Give Yourself Credit For It For This Is What You Were Made For."

HaRav Addes related, "Once we were leaving the house. The Rebbetzin said that he should take an umbrella.

`Ah!' he said `What's an umbrella? Something that gets forgotten everywhere.' I am certain that [his real reason was that] he — on his level — considered that there was some honor associated with walking under an umbrella. He would simply put a plastic covering over his hat and go out like that."

"Two years ago [when HaRav Shlomo Zalman was no longer delivering his daily shiurim in the yeshiva], I called him to ask when I could come over to wish him a shono tovah. `This year you don't need to come,' he said. `It's written that one should go to a chochom who supports [i.e. teaches] a yeshiva and I no longer have a yeshiva.'

This pained me greatly and I travelled to him immediately. When I entered he said, `We agreed that you wouldn't come!'

I said, `Our teacher is not supporting a yeshiva, he is supporting the entire generation!'

When he heard my words he almost wept and said, `You are also one of those who treat me this way. You break my spirit. They call me the "poseik hador."' He was literally close to tears. `I don't know one mishna properly, what "poseik hador"? What are you doing to me? What are you doing to me? What are you doing to me?'"

"Yesterday, HaRav Shmuel Auerbach told me, `Around a month ago a letter arrived bearing the title, "Rabbon Shel Kol Bnei Hagolah." He opened the letter and as soon as he began reading, he threw it on the floor, stamped on it and started to shout, `He's crazy! He's crazy!' I asked him who the letter was from and he said to me `I don't know and I don't care. He is crazy.'

"I asked him why and he said, `Look, he wrote "Rabbon Shel Kol Bnei Hagolah" inside the letter as well. On the envelope it could have been a mistake but not in the letter.' "

HaRav Don Segal related, "Someone who was very close to him told me that once, upon entering the beis haknesses before mincha on erev Shabbos, he saw a notice appealing for tzedaka accompanied by his note of approbation, with a number of titles adjoining his name. He called the fellow over and said, `Do me a favor and take down the notice.' He couldn't bear it."

In order to explain how honor did not cause a humble man to stumble into feelings of pride, HaRav Shlomo Zalman once told his talmidim that he had been present on two occasions when people had made the brocho, `Asher cholak meichochmoso liyereiov,' and everyone had answered `Omein.' (He did not specify over which chochom the brocho had been made.) Did they all cause him to feel proud?

"Or, say a distinguished man enters a beis haknesses where hundreds of people are sitting," he continued, in his characteristic way of bringing things to life. "As he enters, the entire assemblage rises to its feet. (This perfectly described the scene in Kol Torah before musaf on Yom Kippur as all the occupants of a crammed beis hamedrash rose when the Rosh Yeshiva entered.) Have they tripped him up by awakening feelings of vanity in him and making him `despised by Hashem?'

"Of course not!" he exclaimed. "I know without a doubt that those who were blessed over greatly regretted it at the time and said, `Woe to the person about whom people are mistaken!' It vexed them. As for the man for whom hundreds of people rise, his heart breaks within him over such honor."

Indeed, HaRav Segal quoted a relative who said that it was HaRav Shlomo Zalman's habit to enter a beis haknesses through the women's section in order to avoid having those present stand up for him. Once, when he was subjected to this honor, the relative felt HaRav Shlomo Zalman's hand trembling.

"I always used to tell him that people felt bound by what he said but he wouldn't hear of it. Once he said that he had a knack for halacha, nothing more than that." (HaRav Shmuel Auerbach)

An Ordinary Jew

HaRav Shlomo Zalman regarded himself as an ordinary Jew. He related to everyone with respect and warmth, as though they were his equals. He despised the titles and trappings of greatness or being accorded special honor. In his hesped, HaRav Segal cited the Chovos Halevovos who concludes that although a certain degree of humility is necessary in order to achieve any self improvement, it is also the highest possible trait that a person can attain, being the praise accorded by the Torah to Moshe Rabbenu who transmitted the entire Torah to Klal Yisroel.

This trait of humility and self effacement said HaRav Segal, perhaps most typified HaRav Shlomo Zalman, from the beginning of his life through to the end.

Humility was the foundation of his Torah achievements no less than of his character. HaRav Tzvi Kushelevsky pointed out that the "coarseness of spirit" identified by Chazal as an indication of meager Torah learning doesn't only mean physicality, the antithesis of Torah which is spiritual, but self-importance. To explain why this is, he compared a person to a vessel — the thicker the vessel's walls, the less room there is inside for something else to be put in.

HaRav Shlomo Zalman so subdued any personal inclinations that it was possible for him to become completely suffused with Torah and to act as a faithful transmitter of halacha. "If the rav is like a mal'ach, seek Torah from him," say Chazal. Just as mal'ach has no independent ambition besides whatever task has been entrusted to him, a teacher of Torah must annul any personal motives in order to be a faithful transmitter of Torah.

A common misconception regarding the trait of humility is to confuse it with simplemindedness or naivete. HaRav Shlomo Zalman himself clarified the matter through discussion of some stories concerning Rabbi Akiva Eiger, who is noted for his phenomenal Torah greatness and his equally deep humility.

One story concerns a letter to Rabbi Akiva Eiger which addressed him as "Rabbon Shel Kol Bnei Hagolah." When he sent his reply, he also addressed his correspondent as "Rabbon Shel Kol Bnei Hagolah." When the questioner later met Rabbi Akiva Eiger, he protested that he was neither a rav nor a gaon and he was certainly undeserving of such honor. Rabbi Akiva Eiger responded, so the story goes, by saying that since he saw this title on all the letters which he received, he thought it was a standard form of address.

When HaRav Avigdor Nebenzahl once repeated this story to HaRav Shlomo Zalman, his response was that the story was untrue and that it had been invented by maskilim who wished to poke fun at Rabbi Akiva Eiger by insinuating that he was an innocent. Certainly he was aware of his standing in the Torah world and would not have made so light of it by pretending it was a conventional title.

Another story concerns the time when, towards the end of his life, Rabbi Akiva Eiger ruled on a controversial monetary dispute. The side he had ruled against retorted by claiming that the Rav was already old, that his sons had misled him and that he was unaware of the true facts. Rabbi Akiva Eiger responded with a letter which proclaimed his greatness and his authority to rule. HaRav Shlomo Zalman asked how he could do such a thing. Don't we know that he was a humble man?

He used a posuk to prove that there is no contradiction. The posuk states that Moshe Rabbenu was the humblest man on earth. If a Jew does not believe one word of the Torah, he is an heretic so Moshe Rabbenu must have believed this posuk with all his heart. Yet he remained humble.

Certainly, explained HaRav Shlomo Zalman, he was aware of his level, yet the greater the person, the greater his humility. He becomes more contrite and his gratitude to Hashem grows greater and greater. He feels that other people are fulfilling what is expected of them according to their capabilities whereas he is far from doing all that he can, with the gifts that have been granted him.

The mishna in Avos says that "[true] honor is only Torah." There was an occasion when HaRav Shlomo Zalman admitted to having been greatly honored. This was when he had received a long distance call from HaRav Moshe Feinstein zt'l who wished to know his views on a certain question of halacha.

Ish Ho'elokim

"My father hk'm, taught us that whoever doesn't feel what his fellow man is experiencing, is not merely lacking special attainments in kindness, he lacks the basic foundation of a human being." (HaRav Shmuel Auerbach)

"What a shining countenance! He had no need to influence others. He was like the sun. Does the sun influence anything? The sun warms, it caresses!" (HaRav Yitzchok Ezrachi)

Chazal comment on the words `ish Ho'elokim' that the upper part of Moshe Rabbenu was G-d-like while the lower part was human. HaRav Chatzkel Levenstein commented that had Moshe Rabbenu been completely spiritual, he would not have been able to identify with others and participate in their feelings. HaRav Shlomo Zalman was able to bear all kinds of troubles and make do with very little, yet he fully related to others.

HaRav Segal related that a distraught father once called on HaRav Shlomo Zalman and found him eating a bowl of soup. (His receiving hours were his midday and evening mealtimes. He would say that this was when he could see people.) The man explained his distressing situation l'a. HaRav Shlomo Zalman instructed him as to how to proceed and blessed him with success.

When the man left, he was unable to continue eating the soup and he asked his son to bring him a pickle which he was also unable to bring himself to eat. He said, "Blood is spilling from this man's heart. How can I eat soup?" Then, after a moment he added, "But that is how it must be."

He entered fully into what others were experiencing. One of those close to him approached him with a grave problem. A short time before, his daughter had become engaged. However, it had since become clear that the chosson was not the aspiring Torah scholar she had believed him to be and upon whom her heart was set upon marrying.

With a heavy heart, HaRav Shlomo Zalman instructed his friend to cancel the engagement, which had been entered under a mistaken impression. When the father returned home he was told that earlier on the phone had rung and an elderly man had asked to speak to the distressed kallah. When asked who he was, he had said, "It's Shlomo Zalman Auerbach."

With a trembling hand, the girl had taken the receiver. "Don't be upset," he said. "You'll see, you will soon have happy, joyful times."

A bochur in the yeshiva spoke in a way which amused some of his friends. When he complained of this to HaRav Shlomo Zalman, he called the other bochurim and explained to them how serious their behavior was. When they countered that it was impossible for them to contain themselves, he retorted, "So you should have choked!"

When he had to express disapproval, it was done in the mildest of terms. The most severe comment he ever made to a bochur who interrupted his shiur with some irrelevant point was, "You are getting yourself confused!"

If a bochur was really talking nonsense and HaRav Shlomo Zalman himself felt that something stronger was called for, he said, "You are getting very confused indeed!" But that was the absolute limit.

After he delivered a lenient ruling to one questioner, the young man asked whether it was not preferable to act stringently? HaRav Shlomo Zalman repeated the lenient opinion. Nevertheless, the man persisted, perhaps there was room to act more strictly? HaRav Shlomo Zalman repeated himself again. After this had gone on a little longer, HaRav Shlomo Zalman said gently, "Yungerman! Your wife is waiting for you!"

When he was already at an advanced age, he would make the not insignificant trip from his home to the neighborhood of Givat Shaul in order to visit a widow. As he became older, it was increasingly difficult for him to climb the five flights of stairs to her apartment. A neighbor who saw this decided to help and place chairs on the landings. When HaRav Shlomo Zalman saw the chairs he commented that it was harder for him to sit down and then get up again than it was to climb the stairs, yet if he ignored the man's efforts, he may give offense. He therefore sat down for a moment, despite his increased discomfort.

HaRav Yitzchok Ezrachi related the following story. An irreligious couple who had met in chutz la'aretz and had began to attend lectures and shiurim there, decided to come to Eretz Yisroel in order to marry and establish a home. All their happiness was shattered when, in a chance remark, the woman mentioned that she had once had a gentile boyfriend. Her fiancee was a Cohen. There seemed to be nothing to do but friends urged the man to visit HaRav Shlomo Zalman.

It was one o'clock in the morning when he approached the house but, seeing a light in the window, he knocked. He was told that the Rav was asleep but had asked to be woken shortly. When he appeared, the man told his story. HaRav Shlomo Zalman gave the only reply he was able to, and then he began to cry, bitter, uncontrollable weeping which those present were unable to stop. When the man later repeated this story, he described HaRav Shlomo Zalman's reaction as the climax of the entire episode.

However, there was a sequel. Some time later, a visitor from the same country arrived in Eretz Yisroel who knew the gentile boyfriend and revealed that his maternal grandmother had in fact been Jewish and that consequently the boyfriend himself was a Jew, not a gentile. This fact removed any halachic obstacle to the marriage. "It was HaRav Shlomo Zalman's tears," commented HaRav Ezrachi, "that brought that visitor to Eretz Yisroel!"

The greatest testimony to his empathy to others is his by now famous declaration after he lost his wife. When his rebbetzin passed away eleven years ago, he said at the levaya that there was nothing for which he needed to ask her forgiveness. One of his close confidants asked afterwards how such a thing was possible.

He replied, "Actually, all the way to Har Hamenuchos I was thinking perhaps nonetheless there was something, but I couldn't remember anything. Nevertheless, I asked forgiveness before the burial."

The friend asked, "Yet after so many years, how is it possible not to have anything for which to ask forgiveness?"

The reply was, "Certainly we had differences of opinion, as well as various arguments in the course of our life however, I always spoke objectively about the matter at hand. I never expressed myself personally..."

Continued ...