Part I

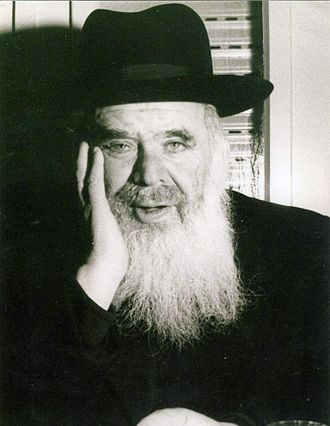

This extensive appreciation of HaRav Chaim Shmuelevitz zt"l was first published in our English Yated in 5754 (1993-94) at the fifteenth yahrtzeit.

To "thirstily imbibe their words" is not a casual statement but a fundamental condition and requisite for Torah study. This is what R' Chaim used to preach. By what yardstick did one measure real thirst? Only if one could testify that "Torah is as dear to its scholars, day by day, as it was on the day it was given upon Mount Sinai." Torah's belovedness renews itself and is anchored in its familiarity and closeness. One's affinity to Torah becomes non quenchable.

R' Chaim used to construct entire shmuessen upon this theme, but above all, he demonstrated it with his example, in his own approach to study. Despite the fact that the entire Talmud, together with the rishonim and acharonim commentaries, fell fluently from his lips, he would repeat every saying and chidush countless times over and again. One could hear him murmuring a teaching of chazal or a halacha in Rambam consecutively, dozens of times.

This was all the more remarkable in the light of the phenomenal amount of knowledge stored in his brain. This was the very same R' Chaim whom R' Chaim Ozer Grodzensky labeled "the [human, walking] library of Yeshivas Mir," rising to his feet when he entered the room. While R' Chaim was yet in Grodno, R' Shimon Shkop would seek his advice upon delicate agunah problems, availing himself of R' Chaim's photographic memory of the many responsa dealing with the topic, which R' Chaim could fish up at will. It was so precise, in fact, that his memory was relied upon when the yeshiva sought to print the Ketzos Hachoshen in Shanghai from a copy with a page missing. And he considered it no feat.

"A genius in the art of review," is what R' Leib Gurwitz zatzal, rosh yeshivas Gateshead, would say. R' Chaim was perennially reviewing what he had learned. And if someone expounded a chidush which pleased him, he would pace back and forth while etching it deeply in his memory through numerous repetition.

R' Tzvi Kahane related a fact he heard from R' Shmuel Charkover, who was R' Chaim's study partner. They were once deeply involved in a complex issue in Talmud Yerushalmi. They explored different approaches until the wee hours of the night. The next morning, when they attacked it again, R' Shmuel was amazed to see that R' Chaim had all the different versions down pat, as if they had just finished summing them up. How could it be? R' Chaim saw his surprise and asked, "What did you do last night after we finished?"

"It was so late and I was so exhausted that I went straight off to bed," replied R' Shmuel.

"I went to bed, too," said R' Chaim. "But not to sleep. In fact, I stuffed the pillow into my mouth so I would not doze off while I reviewed, over and over, the different approaches we had labored over."

Open Your Mouth Wide — And I Will Fill It

Only one who is truly a seeker can attain the level of "They should be new in your eyes each day." R' Chaim regarded this outlook as a prerequisite to achieving anything in Torah scholarship. A person must be "wise of heart" in order to reach the level of "I have put wisdom into the hearts of every wise-of-heart."

Yehoshua waited for Moshe Rabbenu at the foot of Mount Sinai for forty days. He left his home and the nation, which was in his charge, purely for the privilege of serving Moshe those few moments sooner, upon his descent. This characterizes a mevakesh, a seeker, a person with a noble spirit. Hashem is willing to grant such a person everything— he need only open wide his mouth for it to be filled.

When R' Yehuda sought to commence with the honor of the Torah (Brochos 63), he attempted to define the seeker as those talmidei chachomim who wander from one city to another and one country to another in search of Torah. We learn this by comparison, since if the Torah deemed the mevakesh to be one who merely left the camp and went to seek Moshe at its outskirts, how much more so is one entitled to that title if he travels great distances.

During one period, R' Chaim used to give a chabura to a group of older students in Yeshivas Chevron. This was steadily `crashed' by a young outsider who yearned to listen in. Try as they might to prevent him from attending, the others could not stifle his ardent thirst for knowledge. He was adamant.

R' Chaim was deeply impressed, and showed it. He would often turn to the young man in the middle of the lesson and suggest, "Let's hear what you have to say on the matter." He thus sought to raise him in the eyes of the others since he recognized this unquenchable thirst in his character, the essence of the eternal mevakesh.

R' Chaim despised the `smug ones,' those who perhaps studied a bit more than was expected, innovated some chidush and went around with a fat, complacent look that made them feel good for a long time. "It is no wonder that we hear of `crises' and `breakdowns,'" he once noted. "One who is smug is never really happy. He has had his fill. Only one who is thirsty can attain the level of `The ordinances of Hashem are straightforward, they gladden the heart.' He truly revels in every bit of knowledge accrued from one moment to the next."

We would like to present specific vignettes upon this aspect of his personality, but his entire essence bespoke joy. In reply to the questions asked by his chavrusas and talmidim, he would offer a witty repartee which reflected his unwavering happy disposition. He lived in the aura of Simchas Torah all year round.

The building of Mir Yeshiva in Europe

Devices to Counteract Routine

R' Chaim dwelled a lot on the dangers of falling into the rut of routine and rote, that lassitude which freezes a person's emotions.

When Yaakov's sons entered into negotiations with Eisov over the burial Cave of Machpela, they agreed to wait until Naftali fetched the deed from Egypt. The circumstances of their situation, the lengthy and exhausting dealings, completely blinded them to the shocking fact that their father lay in a state of disgrace. Only Chushim, the son of Dan, who was hard of hearing and not privy to the discussion, realized the degree of his grandfather's dishonor.

Upon another occasion, R' Chaim explained that a person must constantly search for ways and methods to avoid the steady routine that dulls one's thinking and extinguishes one's spark of holiness. R' Chaim would point to the Chossid Yaavetz who explains the words of Yechezkel who said that a person who entered the Beis Hamikdash was forbidden to leave it by the same gateway. This was because any act repeated loses its impact and becomes banal and stale.

This is also the reason why our Sages established the different customs of the Seder—all are designed to generate interest and excitement, despite the fact that "we are wise, intelligent and all know the Torah." This is why the telling of the Exodus is in the form of question and answer, why we dip twice, why we remove the matzos from the table and so on—all to create a fresh, stimulating atmosphere.

R' Chaim, himself, used to devise clever ways to inject animation and excitement into his ongoing study and review. In his youth, he would walk his chavrusa back to his lodgings, while creating milestones along the way as stations for repeated review: by the door, again by the gate, once more by the electric pole and so on.

One of the yeshiva's neighbors once went up to the beis medrash during the seder and, to his surprise, found R' Chaim studying with melting sweetness. He approached from behind and listened, in rapt attention. Suddenly, he saw R' Chaim gathering up eight of his tzitzis fringes in hand and saying, "In this particular sugya of a positive commandment superseding a prohibitive one, we have eight different approaches. They are..." He singled out one strand after another, as he reviewed all eight possibilities.

"This is the Entire Man"

Gratitude was a basic component of his makeup and an integral part of his life.

His disciple, R' Chaim Walkin now mashgiach, of Yeshivas Ateres Yisroel, once sought his advice whether to attend a certain function of the yeshiva where he had studied in his youth, a ceremony which would take several hours. R' Chaim said that he was in no position to judge how important his presence might be, but, "You should know that as a steadfast rule— hakoras hatov is the sum total of man."

Gratitude is incumbent even upon one who lacks human intelligence. He used to say that Yosef was charged to see how the sheep were doing. Our sages interpret this to teach that one is obliged to show gratitude. To what extent? Even to inanimate things! Hashem did not bring three of the plagues through Moshe: blood, frogs and lice, because the Nile and the dust had protected him at one time and they did not deserve to be "punished" through him.

Gratitude was one of the hallmark features in R' Chaim's life. He would sometimes go great distances in order to participate in some celebration where he felt his presence would bring joy, in order to show his gratitude for some favor. In his later years, he was once invited by R' Meir Kleinman to the bris of a grandchild. R' Chaim's wife asked him to remain home because she feared it would be too much of a strain. R' Chaim insisted on going: did R' Meir not recite Tehillim in the Beis Hamussar with such sweetness after each of his shmuessen? "I owe it to him!" he declared emphatically.

R' Chaim proved from the teachings of Chazal that one is obligated to show gratitude even if one has only benefited indirectly from one who did so unintentionally! Yisro's daughters should really have been grateful to none other than the Egyptian whom Moshe killed, since this brought about his coming to Midian, where he saved them from their plight.

R' Chaim used to illustrate this in a piquant manner: he once made a special effort to attend the wedding of the son of one of the yeshiva's veteran scholars. When those close to him expressed surprise, he explained that the father had been one of the first Jerusalemites to attend his shiur. At that time, when R' Chaim was hardly known, the lecture hall had been practically empty. "But this man sat directly in front of me, to hide the shame."

He Came to Listen

R' Chaim even innovated a new dimension in hakoras hatov—to show gratitude to the person who enables you to do him good! He would sometimes take great lengths and travel distances to attend the festivities of people who, while they were not regular members of the yeshiva, nevertheless, attended his shiurim. His family would chide him and discourage him from such excesses. "Limit your attendance only to the students of the yeshiva," they would say. But R' Chaim felt that if someone came to hear him, he deserved the appropriate show of gratitude. In other words, one must be grateful to one who is the recipient of your benevolence.

In his talks, R' Chaim used to explain that a qualitative ingredient to happiness in this world is sharing and not being `alone.' A person must seek to attach himself to others, to share their joys and sorrows, to help shoulder their burdens and to give of oneself in every way. This exemplifies the nobler prototype of man, Adam, whose happiness is not complete unless his friend can share it and benefit from it equally. To uphold this concept, he quoted from the author of Kuntrus Hasfeikos, saying, in the name of Mahari Muscato, that even if a person were offered the opportunity to go up to Heaven and gaze upon the heavenly hosts in their ranks and files, he would not derive the full pleasure therefrom until he had returned and shared his experience with his friends!

Adam Horishon had all of Paradise at his disposal, with angels doing his bidding. Nevertheless, Hashem said that "It is not good for man to be alone..." Even Gan Eden is not sufficiently perfect for one who is alone.

He would add that the only way to gain friends is by giving. "One who seeks to cement his friend's affection should occupy himself with his good." No one in the world was as devoted to his fellow creatures as Noach. But in order for him to attain such a level of self sacrifice, it was necessary for him to expend his own money. "Take unto you," the Torah tells us: spend your own money in building the ark and then give your all; only thus will you be worthy of the love of the recipients of your benevolence.

He Gives His Very Soul

To what degree must one love one's fellow creature? Says R' Chaim—by giving all one's heart.

The Angel of Death said to R' Chiya that if he showed mercy to the poor by giving them bread, he should be equally merciful to him and relinquish his soul (Moed Koton 28). What does the soul have to do with giving bread? The Angel of Death knew that when R' Chiya gave to the poor, he actually gave it with all his heart; his very soul was crystallized in that crust. Why, then, should he not give his very soul when that was what he, the Mal'ach Hamovess, desired?

He would often dwell upon the subject of sharing another's burden. Even when one cannot actually help in any concrete form, one should share pain in such a way that he is removing some of it. If this is required of every man, how much more so of the Torah scholar, whom, our Sages said, is required to "become sick" over another's suffering.

The sons of a rosh yeshiva who had contracted cancer once came to consult with R' Chaim about treatment. As soon as they divulged the name of the illness, he exploded into stormy sobs, even though he did not know this man personally. It took the sons considerable time and effort to calm R' Chaim down.

Such genuine concern was not only showered upon a Torah scholar or even a decent Jew, but upon every living creature. One who stood by indifferently in the face of another's suffering must have a blemish in his soul. Such insensitivity can only lead to moral corruption.

When he left Shanghai, R' Chaim spent all day on deck, since it was all but impossible to remain in the stuffy rooms deep in the belly of the ship. Among the other travelers were French officers, whose children ran wild about the deck. R' Chaim would tremble and say, "How can parents neglect their children so? Any false step can send them tumbling into the sea!" He refrained from saying anything until he saw one child playing right by the rope while his father stood by, completely indifferent to the danger. "Reshoim!" R' Chaim screamed, and unable to look on for another moment, descended to his dingy, stuffy cabin.

Continued