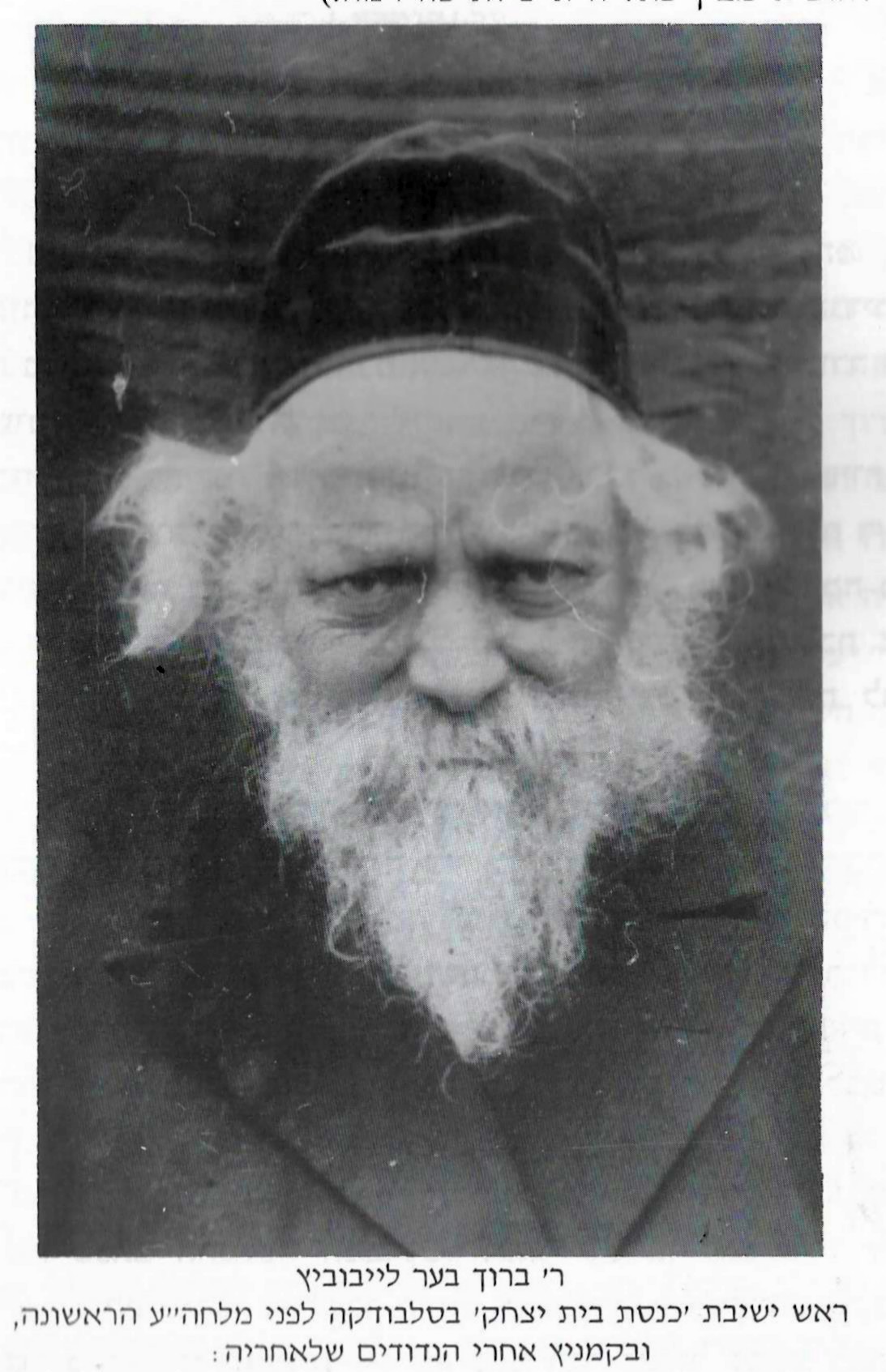

HaRav Boruch Ber Leibowitz zt'l

This was originally published in our print edition in 1994, 28 years ago.

Introduction

R' Boruch Ber's Torah used to pass eagerly by word of mouth throughout the European yeshiva world of ninety years ago. Today, while we possess the four volumes of his Bircas Shmuel which contain his shiurim, we are without the warmth and enthusiasm of his delivery. The language of the printed shiurim is terse and concise and much hard work must be invested in understanding the content. (Recently, several volumes of Chidushei Veshiurei Maran Rabbi Boruch Ber, have been published. These consist of notes of R' Boruch Ber's shiurim made by his talmidim, in a style that is much more easily understood.)

The opinion has been expressed that the difficulty in grasping R' Boruch Ber's meaning is a result of his total, self-imposed submission to the derech of his teacher, HaRav Chaim Soloveitchik. In stifling his own creativity, the argument goes, and sticking to the elucidation of the Torah which R' Chaim had developed, he sacrificed easier conveyance of his ideas for the sake of faithfulness to what he had received.

It is surely no coincidence though, that R' Boruch Ber, who put all his energy into delving deeper and deeper into the meaning of his own and earlier great teachers, derived such immense satisfaction and pleasure from Torah. Who but he, who uncovered the hidden depths of the teachings of rishonim, could enjoy Torah so much? And in fact, he was a mechadesh.

One godol, a contemporary of R' Boruch Ber's, posed the following difficulty. The gemora states that Rabbi Eliezer Hagodol never said anything which had not heard from the mouth of his Rebbe. In Ovos DeRabbi Nosson however, it is related how Rabbi Eliezer Hagodol sat and delivered teachings which nobody in the world had ever heard before.

In fact, the godol answered, there is no contradiction whatsoever. In the teachings of his Rebbe, Rabbi Eliezer Hagodol heard things which nobody else heard. In his work Ishim Veshittos, in the chapter dealing with R' Boruch Ber, HaRav S.Y. Zevin notes how aptly this applies to his subject. The importance of dedication to understanding the Torah one's rebbe teaches: Perhaps this is R' Boruch Ber's most important legacy to us.

Childhood

R' Boruch Ber was born and raised in Slutsk, a town in White Russia. His father, Rav Shmuel Dovid Leibowitz zt'l, was a great talmid chochom and his mother was the only daughter of R' Nochum `Podlivetscher,' a wealthy and esteemed member of the Jewish community in the village of Podlivetsch. R' Nochum doted on his grandchild and devoted himself wholeheartedly to his education. His sincere wish was to see the young Boruch Ber grow up into a godol beTorah.

Slutsk was one of the oldest Jewish communities in White Russia. It was a distinguished community that could boast of having had many gedolei Torah serving as its rabbonim as well as many ordinary householders who were great talmidei chachomim themselves. During R' Boruch Ber's childhood, the Beis Halevi, HaRav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik was the rav, and as a young child R' Boruch Ber accompanied his father on many a visit to this gaon and tzaddik.

As a child, R' Boruch Ber was taught privately. He applied himself assiduously to his studies and was never seen without a sefer in his hand. He also had a reputation for being a tzaddik. One of his teachers was R' Yisroel Yonah, who had also taught the young R' Chaim Soloveitchik. While studying under this teacher, he began formulating his own novel Torah thoughts, which reflected his sharpness of mind as well as his wide knowledge.

At the age of fourteen, he delivered a complex shiur in Slutsk's Kofasker Shul on the topic of shomer shemosar leshomer. This shiur caused something of a sensation in the town and seemed to indicate that a great future awaited the youthful scholar. This promise was indeed borne out, although his genius was to develop along a somewhat different path than that indicated by his early achievements.

Yeshivas Eitz Chaim, Volozhin

Around 5643 (1883), when he was sixteen, R' Boruch Ber arrived in Volozhin. The yeshiva, which was being led at the time by the Netziv and HaRav Chaim Soloveitchik (son of the Beis HaLevi), was in its heyday. The yeshiva's three hundred talmidim were to be found learning in the beis hamedrash, which was known as `the White House' because it was built of white stone. Some would sit and some stand, while others walked up and down the length of the hall holding their gemora in their hands. They all learned out loud, each in a tune of his own. The talmidim of Volozhin enjoyed a reputation for extraordinary application to learning and for their dedication to the goal of becoming thoroughly acquainted with every area of Torah knowledge.

During R' Boruch Ber's first meeting with HaRav Chaim Soloveitchik (henceforth, Reb Chaim), he told him some of his own chidushim. Reb Chaim listened in silence. Only when the new talmid tried to refute something which appeared in the sefer, Beis HaLevi, did Reb Chaim respond tersely with the admonition, "Slutzker, der Tatten darf men farshteien." ("Slutzker, my father's writings must be understood in depth [not superficially refuted].")

When R' Boruch Ber displayed the notebooks in which he had written some other of his chidushim, Reb Chaim remained singularly unimpressed and rejected them all.

Sharp as R' Boruch Ber's mind was, the chidushim he had presented to Reb Chaim did not bear the imprint of the penetrating analytical thought which the shiurim of the rosh yeshiva had introduced into Volozhin. Reb Chaim trained all his mental powers on uncovering the basic building blocks of the sugya at hand, rather than trying to deal—either more or less superficially—with a number of sources at once. Reb Chaim delved into the sugya, probed, weighed, calculated and contemplated. Only after a long and rigorous process, when he was finally satisfied that he had reached the true underpinnings of the subject, would he deliver his shiur.

Even Reb Chaim had initially met with some opposition from the lomdim of Volozhin, who, with their wide knowledge of Shas, would call out to him that there was a different gemora elsewhere which was in direct contradiction to the point he was making. He would patiently reply that he was also aware of that gemora and would proceed to demonstrate that the other sugya presented no difficulty whatsoever.

After an initial period of friction, the talmidim became acquainted with his approach and they would henceforth feel that the brilliant light with which he had illuminated the topic of every shiur revealed the plain, simple—almost self-evident—truth. Even if they emanated from a brilliant mind, Reb Chaim could not approve of chidushim which were built upon sudden flashes of inspiration, rather than painstaking thought and analysis.

Rav Boruch Ber eventually married the daughter of HaRav Abraham Isaac Zimmerman, whom he succeeded as rabbi of Halusk.

The first yeshiva in Slobodka was the famous Knesses Yisrael yeshiva, founded and led by HaRav Nosson Tzvi Finkel in 1882, and named after HaRav Yisroel Salanter. HaRav Moshe Mordechai Epstein was rosh yeshiva there.

In 1897, controversy broke out in the yeshiva. HaRav Finkel was a strong advocate of the mussar approach, but many of the students were opposed to the strong focus on mussar, as opposed to only studying gemora.

The yeshiva split into two, with the group against mussar founding Knesses Beis Yitzchok. The yeshiva was originally headed by HaRav Chaim Rabinowitz (who was later known as HaRav Chaim Telzer). It was named for HaRav Rabinowitz's great father, HaRav Yitzchok Elchonon Spector zt'l, the rav of Kovno.

In 1904 HaRav Rabinowitz left and HaRav Boruch Ber was appointed rosh yeshiva. Under R' Boruch Ber's guidance, the yeshiva grew and expanded. Hundreds of rabbonim, roshei yeshiva and talmidei chachomim were educated in Knesses Beis Yitzchok.

R' Boruch Ber embodied the tradition of Volozhin. In Volozhin, no distinction had ever been drawn between Torah and yiras Shomayim. R' Boruch Ber was reluctant to introduce the study of mussar into his yeshiva because he saw it as a deviation from the path which his teachers had followed. They had been both geonim in Torah as well as exceptionally righteous individuals, despite their never having attached especial importance to learning mussar. R' Boruch Ber opposed learning mussar on the same grounds that Reb Chaim had done so. They simply felt it unnecessary, since they themselves were as balanced and perfect in soul and character as they were in intellect. On the other hand, HaRav Boruch Ber was reluctant to be known as being against mussar and he sometimes spoke in praise of its learning.

The lomdim of Volozhin used to say, "A healthy man doesn't need balm oil and the best sefer mussar is a daf of gemora."

One of the sources that was adduced as an indication that even HaRav Yisroel Salanter had shared this view was a sentence in one of his letters (Or Yisroel, letter #3), "Now, let us examine the matter in a penetrating light—can a man walk without legs? Can he see without eyes? In the same way, Torah and Divine service cannot be firmly established in a man who is afflicted by the disease of the yetzer hora, unless he learns mussar." Mussar was necessary for the afflicted, it was maintained, not for those who were healthy.

Some of R' Boruch Ber's comments on the subject were: "A good Torah discussion (gut redden in lernen) is the best mussar!" "Understanding one of Rabbi Akiva Eiger's comments properly, makes one into a fine Jew!" ("Oib men farshteit gut a svoro fun heiligen Rabbi Akiva Eiger, vert men a ehrlicher yid!") "If one learns `shor shenogach es haporo,' one sees the truth in all its clarity!" ("Oib men lernt `shor shenogach es haporo,' zeht men dem emes far die oigen!")

It goes without saying that no personal antagonism was involved in this difference of opinion. R' Boruch Ber would tell his talmidim that Reb Chaim would tremble whenever he mentioned Rav Yisroel Salanter. The question was not whether mussar was important or not. It was rather, whether or not a clear, sound mind could be taken for granted, so that Torah learning alone would cultivate purity of character.

In R' Boruch Ber's case, nothing symbolizes the synthesis of Torah learning and upright conduct better than the reverence in which he used to repeat the names of his teachers: "der heiliger rebbe, (Reb Chaim), der heiliger Rabbi Akiva Eiger, der heiliger Abaye, etc." When he said their names, he would actually shudder for several seconds, almost paralyzed by the thought of their holiness and righteousness.

Talmidim of Knesses Beis Yitzchok

While the heads of the two yeshivos enjoyed a harmonious relationship, this was not always the case with their talmidim. In time, as many as forty of the Alter's best pupils used to go over to Reb Boruch Ber's yeshiva to hear his shiur. Among them were the young R' Reuven Grozovsky and an even younger R' Aharon Kotler, as well as R' Yaakov Kamenetsky. At one point, R' Boruch Ber's pupils decided to bar the bochurim from Knesses Beis Yisroel from their beis hamedrash.

This friction seems to have originated in the differing financial situations of the two institutions, rather than in their attitudes to mussar. The fortunes of Knesses Beis Yitzchok were precarious and the living conditions of the bochurim were Spartan, whereas things were easier in Knesses Beis Yisroel. They apparently felt that it was unfair that the Alter's talmidim should have the best of both worlds, living in better conditions as well as listening to R' Boruch Ber's shiurim. The visitors however, were not to be deterred. They perched outside on the windows in order to hear the shiur. Due to his small size, Reb Aharon was even able to climb inside through the window.

The Heroism Of Kremenchug

At the beginning of World War One, Czar Nikolai Nikolayevitch forced his Jewish subjects in the western part of Russia, into exile. Initially, Knesses Beis Yitzchok relocated to Minsk where it found a patron in the person of Reb Refoel Shlomo Gutz, son-in-law of the well-known tea magnate, Wissotsky. Reb Refoel Shlomo supported the yeshiva single-handedly. R' Boruch Ber was overjoyed to discover that Reb Chaim was also staying in the city. He was to be found by his rebbe's side day and night and would not even have gone home at night unless members of his family had come to fetch him! When the fighting drew near to Minsk however, the yeshiva had to move on.

R' Boruch Ber was invited to fill his late father-in-law's position in Kremenchug—a town that was known as `the Yerushalayim of the Ukraine.' His yeshiva travelled with him. When the news of the yeshiva's move spread, more talmidim flocked Kremenchug to learn from R' Boruch Ber, despite the danger and hardship of travelling at that time.

The situation worsened. Kremenchug found itself in a no man's land, at the mercy of marauding bands of Ukrainians who roamed the countryside wreaking havoc. The specters of hunger, disease and pogrom loomed over the town. In one chilling episode, the yeshiva was surrounded by the members of one of these gangs. The gang's leader entered and ordered everyone inside the building to follow him. It was only through miraculous Divine intervention that the members of the yeshiva escaped certain death that day.

The Jews of Kremenchug displayed extraordinary devotion to the yeshivos (besides Knesses Beis Yitzchok, three other yeshivos had taken refuge there) that were residing in their town. The townspeople provided all the needs of the yeshivos, to the extent that this was possible in the appalling conditions. This burden fell entirely upon the community since the town was cut off from the outside world and there was no hope of receiving any assistance. There were times when the hunger was so great that members of the community were forced to sell their clothes in order to obtain bread to eat. Even in such circumstances, the bnei hayeshivos were not forgotten and the meager rations were shared with them.

Despite the havoc into which Russian and Lithuanian Jewish communal life was thrown during the war years, R' Boruch Ber's exiled yeshiva remained a bastion of Torah. R' Boruch Ber continued developing and delivering his shiurim.

In 1921 the yeshiva reconvened in Vilna and once again took up residence in the suburb of Lokishok. R' Boruch Ber managed to deliver several shiurim there, with all his customary verve and energy. From Vilna, he planned to move the yeshiva to Eretz Yisroel. Like the Netziv however, he was not to live long after being uprooted from his yeshiva. The physical and emotional strain of the previous months had taken their toll. He delivered his last shiur just ten days before his petiroh.

He fell ill and a week later, on the fifth of Kislev, 5700, he passed away.

During his lifetime, his Torah had spread and was discussed throughout the entire yeshiva world. It was fitting therefore that his levaya was attended the thousands of rabbonim and talmidim who were then taking refuge in Vilna. Perhaps more than any other single figure in the prewar European yeshiva world, R' Boruch Ber personified the pure, endless striving and yearning for wider and deeper knowledge and understanding of Torah. This was his `chidush' and his legacy to all future generations.

[Almost all the information in this account is taken from, Rabbi Boruch Dov Leibowitz: His Life And Activities by Rabbi Yitzchok Edelstein, published in 1957 by Netzach, Tel Aviv. Several other articles were consulted, notably The Kamenitz Partnership by Chaim Shapiro, The Jewish Observer, October 1980.]