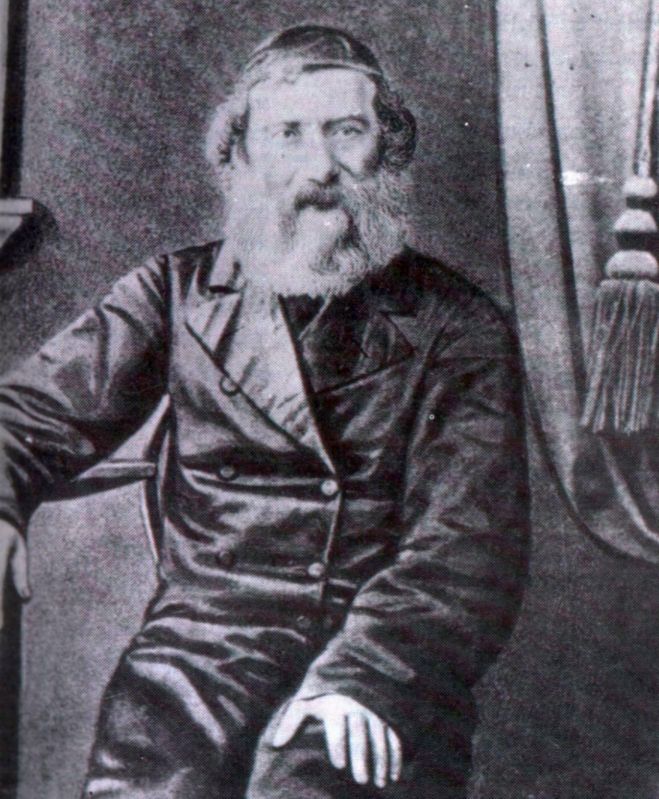

The Malbim

An Ambiguous Response

Sadly, Orthodox Jewry's outcry left the members of the Braunschweig Conference unmoved. They were certainly familiar with their situation, with the leading Jewish personalities of their generation and with the Jewish rank and file, in whose midst they were active. They surely therefore expected a sharp reaction, of one kind or another. They only felt injured by the attacks of those who usually respected them on account of their contribution to research in the field of `Jewish scholarship.'

Among such admirers, the personality of Rav Shlomo Yehuda Rapoport, the chief Rabbi of Prague, stands out. Rav Rapoport (who was known by his acronym, ShYR) was both a believing and an observant Jew. At the same time however, he was also a maskil and he managed to arouse the ire of the gedolim of his time because of his close ties with the pioneering reformers, whose ideas concerning the most basic tenets of Judaism were completely heretical. In his letter to the Oruch Laner, the Ksav Sofer mentions his desire to see the signatures of the Prague beis din appearing on the letter of protest.

"Since, in the province of Bohemia, there is the great and famous community of Prague, whose beis din is headed by Rapoport—together with two other dayanim who are tzadikim and very great Torah scholars, the geonim, HaRav Shmuel Freund and HaRav Efraim Leib Tobols—and relations between us have never been effusive, your honor will forgive me for asking him to send them a special letter, addressed to the beis din as a whole, asking them to sign. It is self understood that this will be extremely effective in the present matter."

The Ksav Sofer's less than friendly relations with the Prague beis din are noticeable in both the letter's style and its content.

Apparently, ShYR's signature never arrived. He chose to remain on the sidelines during the battle against the destroyers of our religion. He sent his direct response to the second Conference, which was held one year later in Frankfurt. After apologizing for not attending, he based his estimation of the delegates standing to execute any practical resolutions whatsoever, upon the halacha that "One beis din cannot annul the rulings of another unless it exceeds it in wisdom and in numbers."

ShYR argued, in other words, that the members of the Braunschweig and Frankfurt Conferences could not presume to change anything, and that their assembling together for that purpose was therefore based upon a mistake.

Such was ShYR's attitude. While he did not actively lend the reformers a helping hand, he left ample suggestion that the Braunschweig delegates' only problem lay in their not being greater than Chazal in numbers and wisdom! Even the wording of his response to them is tortuous and incomprehensible. He wrote, "Even if there is anything in our customs or our laws that needs to amended or renewed, time will achieve that amendment or renewal."

`Little Foxes'

The seeds that were planted at Braunschweig took root and have been producing bitter fruits ever since. Not everything that can be traced to Braunschweig is bitter, though. As in other cases throughout Jewish history, where communal failings prompted great men to launch new spiritual initiatives, which stemmed or even reversed the various destructive ideologies that threatened to engulf traditional Jewry, the tragedy of German Reform also provided the impetus for one of the greatest commentaries on Tanach ever written. Here is HaRav Meir Leibush Malbim's own account of how he came to write this great work.

"Every student knows that the simple meaning of the text and its interpretation according to Chazal's rules, constitute two separate approaches to understanding the verses, which cannot be united. Besides the general wonderment to which this phenomenon gives rise among our people, leading certain lawless individuals to presumptuously try to propound their own theories, which they have failed to do successfully, thus giving rise to the Karaites and the heretics who smashed the yoke, threw off the reins and wreaked tremendous destruction, laying waste a holy people. They vacillated in their approach, sometimes turning to the study of the language and the plain meaning of the verses, viewing Chazal's interpretation as foreign and branding it as unpalatable, while they sometimes were drawn after the homiletic and traditional interpretation to such an extent as to annoy anyone possessing common sense or anyone who sets his mind to understanding scripture.

"In the year 5604 of creation, we heard a voice like that of an invalid; as though suffering the pain of childbirth. It was the voice of Hashem's Torah weeping and spreading out her hands, while her tears lay upon her cheeks because her friends had betrayed her. A few of the pastors of German Jewry acted stupidly and angered Hashem, gathering together to annul laws and statutes, taking counsel against His hidden things. Many leaders ascended, shepherds who consume the flocks they which tend, calling themselves rabbis and preachers, cantors and slaughterers of their communities. All these people assembled in Braunschweig, the Valley of Lime, where they burst the empty jars and the torches were made visible. The little foxes collected with firebrands on their tails and a fire then spread, consuming briars and thorns, burning stacks and standing produce, vineyards and olive groves. It burned in Hashem's sanctuary, between the poles, and it singed the Ark of the Covenant and threatened to destroy the Tablets of Stone and to burn all Hashem's appointed places throughout the land.

"In those days and at that time, I saw and took to heart that it was a time to act for Hashem, a time to build a fortified wall around the Written and the Oral Torah, encircling them with bolted doors so that the lawless ones could not ascend to them and profane them, whether the written Torah, which that evil community views as one of the stories of ancient peoples and whose poetry and style they equate with the poems of Homer and the Greeks..."

Round Two: Frankfurt 1845

The Frankfurt Conference was attended by thirty-one delegates. It was considered an opportune time for discussing the question of switching the language in which Jews prayed from Hebrew to German. The less zealous reformers argued that the retention of Hebrew was necessary for the preservation of a Jewish minority that would be fully integrated, socially and culturally. Geiger and a number of others felt that they drew more inspiration from prayers that were uttered in the German tongue.

Another of the debates at Frankfurt centered upon one of the eternal foundations of the Jewish faith: the coming of Moshiach and the return to Eretz Yisroel. Heresy can assume many different guises and, at Frankfurt, a number of these were proposed. While delegates conceded that belief in the coming of Moshiach is one of Judaism's central tenets, they argued that in the context of integration into modern society this belief necessarily lost its narrow political overtones and instead had meaning only in universal terms, as it affected the whole of mankind.

It is hard to conclude from such pronouncements, whether or not they in fact believed in the coming of an actual Moshiach. It is likewise difficult to fathom the precise meaning of the following declaration: `The Messianic ideal deserves an important place in our prayers but requests for a return to the land of our forefathers and the establishment of a Jewish State should be dropped.'

Which manifestation of the Messianic ideal was left to pray for?

From abolishing prayers for returning to Eretz Yisroel, it was but a short step to abolishing the requests for the renewal of animal sacrifices. The yearly cycle of Torah readings was exchanged for one which took three years to complete the entire Torah, and the haftoros were henceforth to be read in German. The Conference also decided to `permit' organ playing in synagogue, even by a Jew on Shabbos. In deference to the Torah's prohibition against copying the customs of gentiles however, the delegates decided that the precedent for organ playing would be considered—not the Christian model—the magreifa, one of the instruments played by the levi'im in the Beis Hamikdash!

Conclusion

It is difficult to identify any particular move made by Reform throughout its history that marked a point of no return. They were already beyond recall right at the outset, when they abolished the practical observance of certain mitzvos, such as the laws of family purity, conversion, Shabbos and tefillin.

What is most difficult to understand though, is the wish to uproot the most basic aspects of Judaism while simultaneously attempting to fashion a new pseudo-religious Judaism. It is much easier to understand the compulsion to be mechalel Shabbos, which brings many other forbidden things within reach, than it is to understand what prompts the wish to move Shabbos to Sunday. A man who does the first may be a rosho but the second is a fool and is representative of regressive, not progressive Judaism.