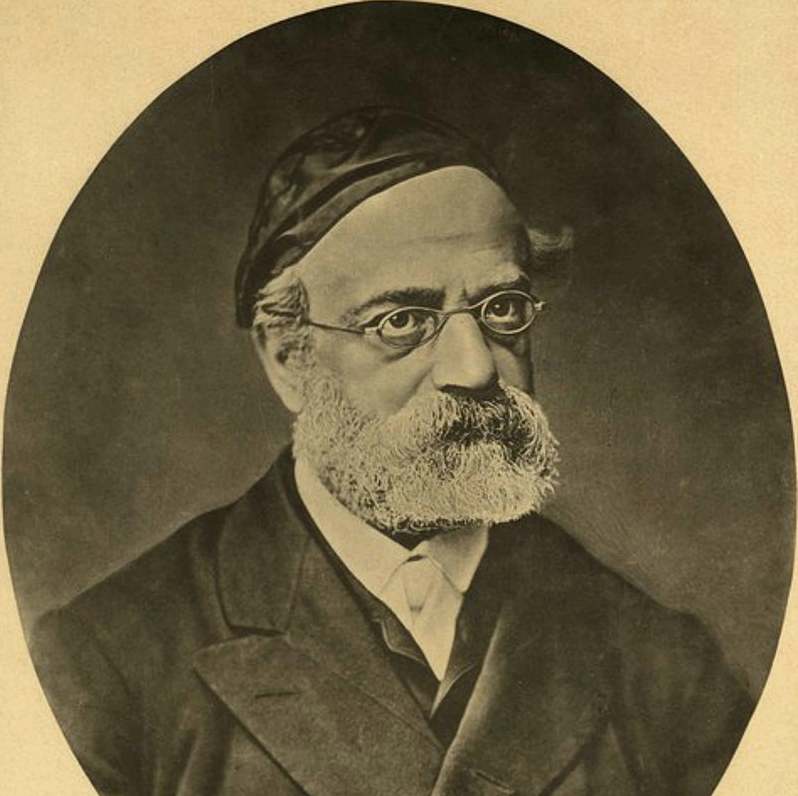

HaRav Samson Raphael Hirsch zt"l

Part II

Part II

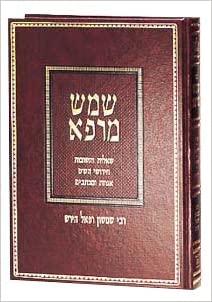

HaRav Shamshon Rafael Hirsch was niftar on December 31, 1888, or 27 Teves, 5649. This year is thus 132nd anniversary of his passing. 27 years ago, we published this essay, marking the publication of Shemesh Marpeh a major study of HaRav Hirsch by HaRav Eliahu Meir Klugman. We are happy to republish it now on the Internet.

Shemesh Marpeh

by HaRav Shamshon ben Raphael Hirsch

edited by Rav Eliyahu Meir Klugman

Published by HaRav Shimon Schwab in 1992

Distributed by ArtScroll

For Part I click here.

Torah Measurements

Another interesting topic in the responsa concerns the question of shiurim, the amounts and measures of various quantities needed to fulfill the mitzvos, for example the kezayis or the ammo. Today there are 2 different systems of shiurim which are commonly accepted: those of R' Chaim Naeh and those of the Chazon Ish. Rav Hirsch states that the middos depend on the time and place, i.e. since chazal were koveya a midda as being dependant on an etzba (the width of the thumb at its first joint) then one must take the "average" middas ha'etzba at that time in that place. As a result, if one finds two places with different middos, it's not a contradiction at all.

He says further that one needn't take new measurements if there is an established tradition of how to be noheig in that place. However, if there's no kabbolo, then, for example, one measures the largest and smallest common etzba and takes the average of these two measurements as his middas ha'etzba. These principles are all very similar to those of the Chazon Ish in the Kuntres HaShi'urim (Orach Chaim 39). He also bases himself upon the same mishna as the Chazon Ish (Keilim 17, 6) that middos are not an exact science but are dependent on opinion of haro'eh but that if a midda was nikba by the chachomim then that remains the shiur.

He does advise that 1) lechumra for matters of public interest such as the shiur mikveh or eruvin, all places in one country should be machmir according to one fixed measurement and 2) it's best to reconcile our size-dependent middos with those being used by the goyim. He put this into practice when Frankfurt became part of Prussia. At that time he proceeded to enlarge the shiur of an ammo from 56.9 centimeters to 62.8 centimeters.

What is of great interest is, as he specifically notes, the wide disparity found even in neighboring places. As mentioned, in Frankfurt the ammo was 56.9 centimeters. In Prussia it was 62.8 centimeters and in Austria it was 63.2 centimeters. The latter, he says, was the midda used there at the time of the Chasam Sofer. These amounts are all much closer to that of the Chazon Ish (57.6 centimeters) than that of R' Chaim Naeh (48 centimeters).

It is worth noting that Rav Hirsch used these measurements lechumra even in the case of a din derabbonon. A case in point was the height of a lechi which is not only a din derabbonon but moreover there is a general principle of halocho kedivrei hameikel be'eruv, we follow the lenient opinion in questions of eruv. This approach lechumra is unlike the opinion of the Mishna Berurah (371:68) who states that in the case of a din derabbonon one needn't bichlal be machmir and one can rely on the smaller shiur beitza.

The Jewish school in Frankfurt established by HaRav Hirsch

In his response, Rav Hirsch goes on to say that he believes the disparity in the quantities was mainly due to the second principle noted above, namely, that the chachomim sought to have their measurements coincide with official government standards. He does, however, note that the place where the sho'el lived actually measured and found the ammo to be 56 centimeters and thus that is correct for his place. He explains that the fact that there is a lack of uniformity is no vice since when chazal said that a certain shiur depends on a certain standard then the standard is related to the root cause of the halacha. For example, the height of mechitzoh is based on etzba'os since the mechitza needed to separate two groups depends on the people's physical height.

Rav Hirsch's grandson, Rav Yosef Breuer, once told me that he measured an ammo to be 20 inches (more than 50 centimeters). Theoretically one should be able to derive from here that the shiur of a tefach is quite close to that of R' Chaim Naeh (48 centimeters) and not close to the middos mentioned by Rav Hirsch. Of course, according to Rav Hirsch this is no problem since middos are time- and place-dependent.

However, it may be more related to the well-known paradox that generally people's etzba measures close to the shiur of Chazon Ish but their ammo, the length from the elbow to the fingertip, seems to be in accordance with R' Chaim Naeh (see Middos VeShi'urei Torah). It was the latter that Rav Breuer zt"l indicated that he had measured.

Letters: Rav Hirsch In Action

If in the section of Teshuvos we encounter an aspect of Rav Hirsch which has previously been almost completely hidden, in the section containing many of his letters we meet an aspect of Rav Hirsch's life which has already been partly revealed. Thus, whereas in his Commentaries we see how Rav Hirsch in a more theoretical setting, here we see Rav Hirsch in action, Rav Hirsch lema'ase. We see his actions and reactions, his initiatives and his responses, his motives and his goals.

The editor states at the outset that the true secret of Rav Hirsch was his yiras Shomayim. This midda is apparent throughout his letters and as such can give one a tremendous chizuk in yiras shomayim.

The gemara says (Brochos 57:), Haro'eh sefer Tehillim yetzapeh lechassidus, haro'eh Dovid bechalom yetzapeh lechassidus — one who sees a book of Tehillim or Dovid Hamelech in a dream can expect piety. Rav Hirsch didn't merely write a peirush on Tehillim, he truly lived Sefer Tehillim. His letters are filled with phrases from Tanach not merely bederech melitza but as expressions of the total emes. If something is said in Tanach or in chazal then to Rav Hirsch that is the whole truth. This seems to be what gave him the enormous fortitude to withstand and fight back against the spirit of his times.

One also sees how important were his yedi'os in Tanach and Jewish history. Thus, he knew that this was not the first merida against Hashem, but rather, a phenomenon with a precedent, a phenomenon which he could thus be confident that Klal Yisroel would live through and overcome. In fact, he says that this was the tafkid of his dor: to overcome the nisoyon of reform and hisbolelus. He thus always felt he had rock-solid ground under him which would serve as a base from which to fight back at the forces of the mordim ba'Hashem.

We also see that Rav Hirsch's battle was fought at the intellectual level and not as an emotional battle. He regularly dissects and rebuts his opponents, he doesn't harangue. Thus, we find his advice to the previous rav in Frankfurt (page 188) on how to react to the local kofrim ba'Hashem uveToraso is to speak "without anger, with no words of cursing or accusation." He should just speak the truth as it is and his words, "will be heard from afar and be accepted with praise." He concludes that once one has done his duty as a mochiach then, "the rest is in the hands of Hashem."

This is similar to what Rav Hirsch writes in the posuk in Tehillim, "Betach ba'Hashem va'aseh tov" - "Entrust the fate and the outcome of all your endeavors and aspirations to G-d and aseh tov, your only concern should be to do good wherever you can and as much as you can."

The First Reform Conference

In this volume we read his reaction to the infamous Braunschweig Conference. The Braunschweig Conference was a conference of "rabbis" which purported to "officially change" many of the yesodos of Judaism.

Writing to Torah-true ba'alei batim Rav Hirsch said that, even if today we can't control the masses of Jewry and we don't have the upper hand, nonetheless, we are to learn the lesson of Chanukah. One doesn't give up but ner ish ubeiso, each person has a responsibility and the koach to withstand the outside forces by strengthening his own ner ish ubeiso (page 194). He says that no matter how many people oppose Hashem, nonetheless "rabbim heimah itonu me'asher imohem - ki itonu kol hadoros vechol hadoros habo'im". We are the real majority since on our side are all the generations past and future. We have a tradition, we have a continuity, we have a future. They are a passing phenomena who have no past, no future. It is most interesting that these are the same arguments used by HaRav Shach in discussing the kofrim of today - the Zionist kibbutzniks.

Rav Hirsch goes on to write that in the end the Reform will be no more, whereas those who stand true to Hashem have bought a future: "Hakoton yihiyeh le'elef vehatzo'ir legoy otzum." He concludes (page 196) with an appeal to his opponents and tells them that they won't succeed in becoming like the goyim (which was their goal) "ho'oleh al ruchachem hoyo lo tihiyeh, lo nihiyeh kagoyim asher sevivoseinu... vetachas asher dimisem lehashpil kovod chachomeinu... kein yikar kovod chachomeinu z"l ad olom." In the end they too will, aderaba, bring about a kiddush Hashem. However, as Rav Dessler put it, they won't build the kiddush Hashem but the kiddush Hashem will be built on them.

How prophetic his words were when, less than 100 years later, Hashem brought out how clearly "lo nihiyeh kagoyim" and KesheHashem osse din baresho'im Shmo misgadel umiskadesh. He also wrote to the posh'im of his day the same words used by Yechezkel in his reference to the posh'im of the dor ha'churban (Yechezkel 20).

In the same vein (page 198) he writes about 20 consecutive lines of various pesukim from Tanach and says, "what can I say which hasn't been said by Hashem and what can we add to his words!" The words of the Novi are eternal and they contain the proper analysis and reaction to all events.

Again the fact that he was in the minority left him unperturbed, this was in a sense a chizuk because this had been foretold by the Nevi'im, "halo yisboreru veyislabnu viyitzorfu rabbim," (based on Daniel), "ve'od Beis Yaakov asiriya veshovo vehoyso levo'er ko'alo veko'alon asher beshaleches matzeves bom zera kodesh matzavta" (based on Yeshaya). There is a prophecy that the Jewish people will be weeded out time after time. This is similar to R' Akiva's reaction to the Churban (gemara at the end of Makkos). To Rabbi Akiva, the Churban gave a chizuk. It's a kiyum of the divrei haNevi'im and, therefore, is mechazek us in our conviction that likewise, the other words of the Novi will transpire.

The epic fight Rav Hirsch waged against joining with Reform in a single kehila is timely as well. Unfortunately, the war has not yet been concluded. In our day we still find, "Orthodox" leaders who don't see the danger and the iniquity in joining with the kofrim umordim ba'Hashem. In the letters, Rav Hirsch quotes from gemoras telling how osur it is to join with minnim, so much so that one has to stay further away from minnus than from avoda zara (Avoda Zara 17a). R' Yishmoel told his nephew it's better to die rather than be healed by a minn (Avoda Zara 27a) and if someone is the object of a deadly pursuit one may flee to a beis avoda zara but not a beis minnus (Shabbos 117a).

Rav Hirsch argues that our joining with minnim sanctions their institutions, is mechazek ovrei aveira and gives the impression that there exists more than one approach to Judaism. These arguments are as timely today as they were in 1877!

I would venture to say that we see in Rav Hirsch a living kiyum of the gemora at the end of Makkos, "bo Habbakuk vehe'emidon al achas: vetzaddik b'emunoso yichye. Emunah is everything, it circumscribes the whole Torah and it is the life of the tzaddik — as it was and is the life of Rav Hirsch.

The posuk says (Tehillim 37) "betach ba'Hashem va'aseh tov shechon eretz ur'eh emunah." Rashi says on re'eh emunah - to'chal v'tisparnes mischar ho'emunah shehe'emanto beHakodosh Boruch Hu, lismoch olov vela'asos tov. One can truly live off of one's emunah in Hashem when it is strong. So it was with Rav Hirsch. He was and is being ochel umisparnes mischar ho'emunah. As Rashi says in Chumash (Shemos 14:15) "Kedai hi zechus avoseihem, veheim, veho'emunah shehe'eminu bi veyatz'u, likro'a lohem hayom. Emunah is so powerful that it could tear open the sea, make a kri'as Yam Suf, so it could certainly be poseyach libbo shel bnei odom and be machnis the words of Rav Hirsch into everyone's heart.

The tombstones of HaRav Hirsch and his wife

Concern For World Jewry

However much Rav Hirsch was involved in the fight against Reform, one finds he was also a world leader and involved in all aspects of Klal Yisroel's welfare both within as well as outside Germany. One example which is brought to light in the present volume is Rav Hirsch's involvement as one of the prime forces in the fight to save Russian Jewry.

The time was 1881-1884 and the Russian government abetted a series of pogroms against its Jewish population. At the request of Rav Yitzchok Elchonon, Rav Hirsch became the leader of the rescue battle being fought outside Russia.

Of particular interest are the methods used by Rav Hirsch. He took a cue from Yaakov Ovinu and attacked on three fronts: bedoron, beTfillah, uvemilchomo — appeasement, tefillah and war. We read about a Yom Kippur Koton in Frankfurt with thousands of people fasting. People remained in shul all day, as they do on Yom Kippur, and davened and cried for the Russian Jews. Rav Hirsch himself poured out divrei his'orerus to the community for about three hours. Money was collected for Russian Jewry. People were mekabeil to be mischazek in kiyum hamitzvos and a number of treif slaughter houses closed down!

To us this should be truly amazing. Even when we were in danger in the Gulf War and there were kinussim, atzros Tefillah etc., we didn't witness such an event and we must realize Rav Hirsch was living in "enlightened" Germany and we're living in Eretz Yisroel with bli ayin hora, revovos of Torah-true Jews.

Even in those days, the German response to the troubles of their Russian brethren was so amazing that, as Rav Klugman notes, Rav Simcha Zissel was moved by it to write an entire ma'amar (see Or RaShaZ, number 39) to his son explaining what gave them the koach to do such a thing and what we can learn from it and how we should be mesakein our penimius so that we too should acquire the kochos hanefesh to behave in such a lofty manner.

In this effort, Rav Hirsch used Tefillah for two purposes. One was the obvious, the power of beseeching Hashem, and the second was to exert political pressure, by means of the media and public opinion, on the Russian government. Thus he organized it so that different cities would hold Tefillah gatherings on different days, and that these various events would appear spontaneous. He reckoned that these "happenings" would be reported by the media and since these events would constantly "make the news," they would hold public attention and thus bring pressure to bear on the Czarist government.

On the other front he attempted to influence the Czar by means of the latter's relatives, the German Kaiser and Queen Victoria. He thus used flattery and all other means available to persuade them to influence the Czar as we read in his letter to the Kaiser.

In this campaign we see further how he is completely mevatel himself to the HaRav Yitzchok Elchonon who was the leader of Russian Jewry. Thus, although he was already in his mid seventies, Rav Hirsch writes, "I am prepared to listen to your advice and attempt to do all I can." This is characteristic of a sholeit berucho. When necessary he is willing to stand up and fight, but when the occasion demands he can completely subjugate himself to the directives of others.

His whole life was bitul retzono to HaKodosh Boruch Hu. Rav Hirsch understood that the injunction "bateil retzoncho mipnei Retzono" sometimes entails standing berov ga'ava and fighting, and sometimes calls for total hachno'ah. In Rav Hirsch we see the application of the mishna in Avos "bateil retzoncho mipnei Retzono kedei sheyevateil retzon acheirim mipnei retzoncho." People will give in to you if you completely subjugate your desires to the will of Hashem.

As was said at the outset, in the span of an article one can only touch on some aspects of this truly monumental sefer. There are sections such as the didactic biography of Rav Hirsch and the peirushim on the gemora which we haven't even touched upon and there is more even in the sections which we have dealt with. But yilmod sossum min hameforash: it is more of the same kind of fascinating and important material that we have presented here. It is all well- organized, clearly presented and beautifully produced.

The world owes a debt of gratitude to all who have made this work possible and first and foremost to the publisher, HaRav Shimon Schwab zt"l, and the tireless editor Rav Eliyahu Meir Klugman. Yasher kochachem!

For Part I click here.